THE TREASURY OF ALEXANDER BIN-NUN

Forty years ago, R’ Alexander Bin-Nun wrote fascinating notes with deep Chassidic explanations along with stories of Chassidim that were not well known. * The Rebbe saw these notes and told him to publish them. Unfortunately they disappeared and were only found recently and given to Beis Moshiach to publicize. * In the following article there are stories of Chassidim and especially, his memories of the Rebbe’s father, R’ Levi Yitzchok Schneersohn, whom R’ Bin-Nun used to visit. * Presented for Chof Av.

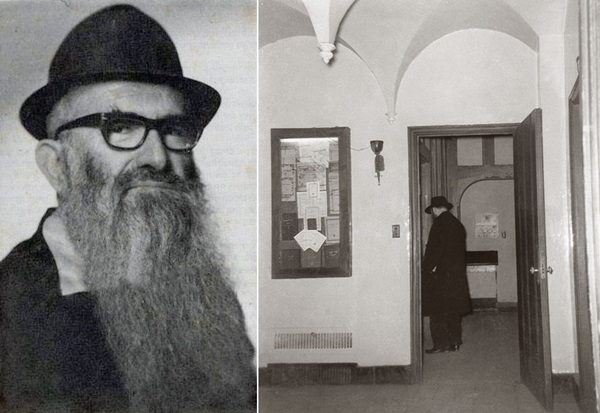

Alexander Zushe Bin-Nun | The Rebbe at the entrance to his room in the early days of his nesiusINTRODUCTORY LETTER BY RABBI BIN-NUN

Alexander Zushe Bin-Nun | The Rebbe at the entrance to his room in the early days of his nesiusINTRODUCTORY LETTER BY RABBI BIN-NUN

B”H

8 Kislev, The Luminous Month, 5739

Raanana

To my brothers and fellow T’mimim, Chassidim, greetings,

1-For a number of years now, talmidim from Tomchei T’mimim yeshivos in Eretz Yisroel and even ziknei Anash, teachers and madrichim, have asked me to write my memories of my youth when I learned in Russia in the Tomchei T’mimim in Nevel and Charkov, and what I heard in private by the gaon and mekubal, man of G-d, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok, the Rebbe’s father, when I was in his city. And what I heard in yechidus by the Rebbe in 5723 and 5729, and the wondrous stories and explanations that illuminate the eyes and soul from the mouth of the Rebbe spoken to those that turned to him in his room.

2-In particular, my memories of the Rebbe’s holy father. I was like a ben-bayis (member of the household) and served him and Rebbetzin Chana in his home in Yekaterinoslav in Ukraine, albeit just a little, in 5687, from Rosh Chodesh Adar until 18 Elul, the summer when the Rebbe Rayatz was arrested and released.

3-However, let it be known that since fifty years and more passed since then, and I was only 16-17 years old at the time, it is possible that I did not understand well and proper and with exactitude the ideas and categorizations of the mekubal and gaon, father of the Rebbe. I may have erred both in content and explanation.

Another possible pitfall that concerns me when I accepted this responsible and exclusive mission to convey to the generations what the great Chassidim said in previous generations is that they spoke their holy words in Yiddish and I translated it into Lashon Ha’kodesh. I may have left out or added or wasn’t accurate and did not plumb the depth and content of the matters and concepts, perhaps even likely so.

Therefore, I am requesting that if it is found in books or if you heard it explicitly and clearly otherwise or with some change from what I write, I do not maintain that you should accept my version; rather, I assume the mistake is mine and forgive me.

4-My notes contain two chapters: one chapter contains explanations and categorizations that I remember clearly from the one who said them, as well as the place and year. The other chapter contains explanations and categorizations in concepts and “observations” in the teachings of Chabad which I heard and learned. However, I do not remember clearly who said them and in which books these things can be found. Of course, I am grateful and thankful from the depths of my heart to all the wellsprings from which I drew and drank of their clear and holy waters, and may they be on the receiving end of blessing.

5-May Hashem grant that I properly convey the inner intent and the truth of the Torah of our holy Rebbeim and that, G-d forbid, no mistake go forth in my recorded writings to those who read them, because my entire goal is to spread the wellsprings of Chabad to the next generation, to those who were not there and did not see the “lions” of the holy fraternity.

Furthermore, perhaps Hashem will grant me the merit, that by publicizing these few memoirs of mine I will provide nachas to the Rebbe, “the tree of life.”

6-I thank Hashem for granting me the privilege of spending time under the roof and in the proximity of the gaon and mekubal and man of G-d, R’ Levi Yitzchok, father of the Rebbe, in the summer of 1927 in his city and beis midrash when I studied the holy work of sh’chita with my uncle, R’ Yitzchok Goldschmidt.

Alexander Zushe Bunin (Bin-Nun)

Student in Tomchei T’mimim from 5683-5689, in Russia

ON THE SPOT, THE REBBE ANSWERS A 100 YEAR OLD QUESTION

I heard from the shochet, R’ Gordon: A very old rav went to the Rebbe with a question to which he had not yet found an answer. The strange question without an answer was asked in the days of his father and the days of his grandfather, 100 years earlier. It was asked of g’dolei ha’dor like the Malbim, the Netziv of Volozhin, the gadol of Minsk, R’ Chaim Brisker, the Maggid of Kelm, R’ Yisroel Salanter and others. None of them had an answer. He requested of the Rebbe that before he died, he should answer the question that was passed along to him by his grandfather and father. This was the question:

There is an enigmatic Midrash on the verse, “and where is the sheep for the olah (burnt offering),” which says, “As it is written, ‘A person worries about ibud damav (lit. losing his blood, though usually understood to refer to losing his money) and does not worry about ibud yamav (losing his days).’” What is the connection between the verse and that aphorism?

The Rebbe answered him on the spot: Yitzchok said, I am the bechor (firstborn) and a korban bechor is kodshim kalim (sacrifices of a “lighter” holiness). Kodshim kalim can be slaughtered anywhere in the Azara and their blood requires just one application as long as it is done towards the foundation of the altar. Since Yitzchok was a firstborn, the sacrifice of Yitzchok had to be according to the laws of kodshim kalim.

On the other hand, the olah burnt offering is one of the kodshei kodshim which needs to be slaughtered on the north side (not just anywhere) and the blood must be received in a special vessel in the north, and the blood requires two applications, etc.

If so, said Yitzchok, “where is the sheep for the olah?” i.e., how will you spill my blood and how will you sacrifice me, as a korban olah or as a korban bechor? There is a big difference!

This is why the Midrash says, at this awesome moment, Yitzchok worried about his blood, whether it would be poured on the altar as a bechor or as an olah, and was not concerned about losing his days.

That was the Rebbe’s answer and the Chassid Gordon said: The rav who asked the question left the Rebbe’s room mumbling, “A gaon, a gaon! Like a Tanna, gaon and kadosh, rashkebhag,” and he fainted. For 100 years, his grandfather and father had looked for an answer and hadn’t found one, and the Rebbe answered him then and there!

MESIRUS NEFESH IN CHINUCH

When I had yechidus with the Rebbe on 3 Cheshvan 5723, I asked: What is mesirus nefesh for chinuch? How can I know whether I have it or whether I need to operate with mesirus nefesh for the education of Jewish children?

The Rebbe’s answer was: Mesirus nefesh means that after you accomplished something, you feel it was hard and entailed unusual effort only in retrospect. Not like the mistake the world makes, thinking that when a person feels that things are hard and there are obstacles in fulfilling one mitzva or another, that this is an indication that he is doing it with mesirus nefesh. This is not so; rather, when it goes easily and a person does not see or feel difficulties, and he does the mitzva, it’s a sign that there was mesirus nefesh in that action. Otherwise, how did he achieve and succeed despite the impediments?

But when it’s hard and he struggles and sighs, that is human nature and not mesirus nefesh.

WHY DOES A CONVERT HAVE TO IMMERSE IN A MIKVA?

A story which I heard from the principal of one of the departments in Yeshiva of Flatbush in Brooklyn goes as follows:

An old acquaintance went to him and told him about a family tragedy. His nephew was about to marry a gentile woman. She was a highly educated and wealthy woman from a distinguished family.

They tried to convince her to convert so as not to bring a tragedy upon the old grandmother and the entire family. Although they were not Orthodox, they still did not believe in intermarriage.

The fight went on and on and in the end, the woman agreed to convert but only under certain conditions, namely, that the act of immersion be explained to her. If it did not make sense to her, she would refuse to convert and would marry in a civil marriage.

Of course, they began bringing her to rabbis and scholarly people and even to Admurim, so they could explain t’villa to her, which conversion requires. But everything they said did not satisfy her demand for logic. She insisted she still did not understand the reason for it.

Mysticism did not convince her, nor did hygiene, and tradition did not obligate her. And so, the tragedy was imminent and the family members were beside themselves.

The principal hesitantly advised his friend to convince the prospective convert to speak to the Lubavitcher Rebbe who would give her an answer that would satisfy her.

At first she was reluctant. “Another rabbi, another Rebbe. I am tired of these nerve-wracking visits,” she said petulantly. She was unused to being in such religious environments.

In their despair, they accepted my advice and convinced the woman that this would be the last time they would suggest that she meet with a holy man, rav, or Rebbe. She agreed and after much effort was made through the secretaries, she had an appointment with the Rebbe.

When she arrived for the meeting, her look and manner were haughty and she was completely embittered about Judaism.

After a while, she emerged from the Rebbe’s room like another woman. She glowed with happiness and in a soft voice she said to the people there, “Here, in this small room, shines the sun of humanity and Judaism.”

When she returned home, she surprised her fiancé by saying: The Rebbe not only convinced me to convert with immersion, but far more than that. I am postponing the wedding because I want to be a kosher Jew. I will convert properly and you too, my future husband, don’t be a Reform Jew without Torah and mitzvos; become a baal t’shuva!

Of course the entire family was stunned and wanted to know what the Rebbe had said to her that changed her mind so completely. This is what she said:

The Rebbe told me that as a learned person, surely I know that a conversion is a rebirth. Conversion is not merely knowledge of Judaism and performance of mitzvos but first and foremost an act of birth, meaning, just as a baby at birth disconnects from its mother’s womb, so too the convert disconnects from his or her spiritual, cultural, and biological past.

Since the conversion process is like a birth, just as with a birth, it is natural for blood and fluids to appear when the amniotic fluid the baby had been in pours out, so too, when a person converts, he needs to shed the blood of circumcision and immerse. When a woman converts, she enters the water as a gentile and then emerges from the mikva as a baby who is born. Just as without water a birth cannot occur, so too, a conversion cannot happen without immersion.

The Rebbe concluded: Go and immerse because only through immersion will you enter the gateway of Judaism.

She was convinced by what the Rebbe said and performed a genuine conversion and till today, their home is kosher and they are connected to Chabad.

The principal concluded his story: The Rebbe to me is like the sun which illuminates reality. He is an illuminating light, a golden menorah, with his teachings, his wisdom, and his holiness. He is truly a “man of G-d.”

RABBI LEVI YITZCHOK ON THE FUNCTION OF DARKNESS

Once, as I walked from the shul with the Rebbe’s father who was known by the Chassidim as R’ Levik, I think it was Rosh Chodesh Iyar 5687, he stood there and turned to me and said, “Darkness does not define the light. That is not its function. Darkness highlights the light.”

WHY A BEN ADAM AND NOT A BEN OFOR?

R’ Levi Yitzchok once asked me: Man was created from the ofor (dust) of the earth and it says, “for you are dust and to dust shall you return.” So why is he called “ben adam” and not “ben ofor” or “ofri”? Especially when the adama (earth) was cursed and Kayin was called an “ish adama”?

Before telling you his answer, I will describe his image that remains before me like a living image, luminous, clear and sharp, like today, like yesterday:

He stood, and his soft, caressing gaze rested upon me. His blue eyes were sometimes sharp and piercing like a skewer, like an electric charge, so penetrating that I was afraid of his gaze. And sometimes his gaze was soft, caressing, smooth, soothing, drawing one closer, and a twinkle of irony and heightened cleverness over and above that of the person the rav was speaking to.

His bearing was erect, his body upright and athletic. His small, handsome head rested on solid broad shoulders. His gait was slow, calm, sure. He walked lightly and firmly, unlike other rabbis whose walk was hasty and nervous. Even under the terrorist regime he walked like a prince, like an heir of the realm. The walk of a king, a ruler, confident and calm. Whoever saw him felt that Rav Schneersohn sensed his own power, and the rare and wondrous self-confidence he had.

He looked at me and said: If a person was called ofri or ben ofor, his essence, traits, and character would be dust, sand, inanimate, unchanging matter. Contrariwise, the name adam, although it comes from adama-earth, has another meaning, adameh – to resemble, “I resemble the Supernal One.”

That means that a person needs to know, recognize, and sense that he has the ability to correct himself, to change himself. A person can turn himself from a dust-like creature into a lofty being. This is why we are called adam, to remind us and demonstrate that we are not merely dust, a natural creation, but an adam – I resemble the Supernal One, above the natural, elevated above all creations in nature.

THE YECHIDUS OF BORUCH SHOLOM WHEN HE WAS THREE DAYS OLD

In 5681, I heard from R’ Mendel Voronov the following story:

When the Tzemach Tzedek’s first son was born, R’ Boruch Sholom, on the third day the Tzemach Tzedek went to the doorway of the new mother and asked for a little time with his son. This astonished the midwife and his wife, who was the daughter of the Mitteler Rebbe, because it was a tradition in Beis Rebbi that the child was taken out of the mother’s room only for the bris mila. And it was the tradition that the Rebbe did not go to the new mother’s room and did not see the baby until the bris.

They tried to prevent him, but the Tzemach Tzedek insisted. The baby was given to him in his diaper. The Tzemach Tzedek took the three or four day old baby to his room and people could hear the sound of singing with d’veikus and sweetness along with a sort of dance, a tapping of the feet.

After a while, the Tzemach Tzedek came out and gave the baby back to his mother. His face shone with exceptional joy. All the old and young Chassidim heard about it and they all wondered about it, especially the “yechidus” with the infant who wasn’t even circumcised yet.

On the day of the bris, the Tzemach Tzedek saw that everyone, especially the elders, looked bewildered. The Tzemach Tzedek responded, with a captivating holiness on his face: Chazal say (Kiddushin and in the Zohar) that “there are three partners to a person: Hashem, his father and his mother.” There is no other mitzva where Hashem is a partner, only in the birth of a child. If so, how shall I not rejoice when I received such a partner such as Hashem!

You can well imagine how great the excitement was after the Chassidim heard these holy words from the Tzemach Tzedek.

R’ LEVIK’S WONDROUS EXPLANATION

In the summer of 1927, between Nissan and Elul, one of the G-d fearing locals went to R’ Levi Yitzchok, I think he was a Lubavitcher, and poured out his heart about not being allowed to teach Torah in the city. The chadarim were closed, the teachers were in hiding and even the parents of children who learned Chumash and Gemara were arrested. He wrung his hands as he concluded with a cry, “Rebbe, what do we do?”

The rav got up, went over to the man, and spoke to him as one tells a secret. This is what I heard:

Dovid HaMelech in T’hillim, 119, says, “A time to do for Hashem, they have made void Your Torah.” The simple meaning is, when a cruel regime abolishes Your Torah and it is impossible to learn Torah because they interfere, then the thing to do is “A time to do for Hashem” – we must do good deeds. Mitzvos can be done even while the decree against Torah study is still in force and if we start with good deeds, with G-d’s help, we will also attain Torah study (which is a wondrous explanation of this verse).

AND IT IS OVER THIS THAT I CRY

I remember how one time, on a hot summer’s day, the rav sat in the dining room near the long table and wrote. I stood on a plain chair and organized the huge library. I remember the many windows, the white curtains, and the sparkling cleanliness which all reflected the light and the rays of the sun, and the rav in fine spirit.

A breeze blew a sheet of paper off the table and the paper fell on the floor near the bookcase. The rav did not notice. I sprang down with the energy of youth and with holy trembling, or more correctly, with trepidation, I picked up the paper to give to the rav. It wasn’t every day that “a miracle occurs” that I would be standing so close to the rav and could serve him. But the rav did not see that I had picked up the paper and my glance fell upon these lines which I will never forget:

“And my heart is hollow within me” – libi chalal b’kirbi form the acronym of chalav/milk. Mother’s milk is considered not kosher but without milk a baby cannot live. This is what Dovid maintained when he said, “my heart is hollow within me,” “and with sin my mother conceived me.” At the end of the paragraph, in smaller letters, it said “and it is over this that I cry.” (A shudder went through me and goes through me till today – perhaps I erred, may Hashem help me.)

DOCUMENTING A SECRET MEETING IN NEVEL

In 5684, when I learned in Nevel, I ate teg in the summer and on Thursdays I ate by the esteemed Chassid, the “prince” of Chabad, R’ Meir Simcha Chein, who was a baal avoda and whose t’filla was amazing and spellbinding. In Nevel in those days, there were few baalei avoda.

One time I walked into the foyer and sat down to eat supper. In the big room there was a zitzung (secret meeting) about the many hardships and sorrows experienced by the yeshivos because of the cursed Yevsektzia, which brutally oppressed all those who learned Torah and every father of a child that was sent to learn could expect to be arrested and fined.

If my memory is not mistaken, those attending this meeting were: R’ Peretz Laine, R’ Itzke Leima’s, R’ Yona Cohen Paltaver, R’ Gershon Ber Levin, his brother and my uncle, R’ Yisroel Levin, R’ Yisroel der katzav (the butcher), the Moreh Tzedek R’ Refael Cohen, the brother-in-law of Folya Kahn, the son of R’ Boruch Sholom Moskover, and the gabbaim from the yunger minyan and the kleiner minyan.

R’ Meir Simcha Chein sat at the head of the table. He was a nice looking man, of erect bearing and with very wise eyes. He spoke very little, had a rabbinic forehead and a long beard the color of brown tobacco.

The gist of the conversation that I overheard was they all spoke emotionally and sorrowfully about Eisav the Wicked who plotted against the chadarim. There was tremendous fear of anticipated arrests for whoever would be caught teaching or giving a shiur in Gemara, and the sheep of Yaakov were scattered without pasture and without a shepherd.

[To be continued.]

********

I repeat the conversation not in Yiddish as I heard it, in order to be brief and my translation is loose and I hope I don’t distort anything in the transmission. The sorrow and feeling of no-escape was heard and felt and who, if not we the b’nei yeshiva, knew and felt and encountered these persecutions.

Then there was the deep, clear voice of R’ Meir Simcha Chein: In the sidra it says, “And the children struggled within her and she [Rivka] said, if so, why me? And she went to seek G-d.” There are two questions here. First, why did Rivka Imeinu go to seek G-d rather than the doctor or midwife? Second, Rivka knew that she was carrying twins for she suffered because they struggled within her. If so, how did it reassure her to be told, “there are two nations in your belly?”

Third, what Hashem said is surprising for who cares who will serve who, the oldest to the youngest or vice versa, when her complaint was “and they struggled” and “why me?”

I think R’ Meir Simcha raised his voice a bit when he said: Chassidim! Rivka Imeinu knew that they weren’t just any children in her stomach. She had left the house of Lavan not to give birth to just any twins, but to be the wife of Yitzchok, an “olah tmima” (perfect offering), and to take the place of Sarah Imeinu. So Rivka knew even before this that her two children were two nations – holiness and the “other side,” good and bad. Her question of G-d was, is it possible that both are equal and one won’t overcome the other, that holiness will not overcome evil? For she felt them struggling within her without one clear victor; this was her fear. It wasn’t the pain of a difficult pregnancy that made her seek G-d, but her wondering how G-dliness and evil can be equally strong.

To this, Hashem answers: Although there are two nations in your stomach, one nation will overcome the other, and the older one (Eisav) will serve the younger (Yaakov). This calmed her, for G-dliness and holiness would vanquish the sitra achra and Satan. And so it will be! Concluded R’ Simcha, with his deep bitachon, “We must do and do more” and the strength of the Rebbe strengthens us and they will continue to learn Torah and Chassidus.

I did not hear the rest of the conversation. I hurried to a shiur in the tractate Gittin which was given by R’ Yudel Eber or Berel Kornitzer in the women’s section of the kleinem minyan along with my friends: Lazer Lazarov, Notke Gurary, Hillel the son of R’ Itche der Masmid, Yosef Benshikovitzer, Shmuel and Dovid the sons of Chonye Morosov, Asher Batumer Sasonkin, Hilke Asimov and the oldest son of Shmuel Levitin and others.

HOW WAS THE GLAZIER BETTER THAN THE PHILANTHROPIST?

In Tishrei, when I stayed at the home of the Rebbe Rayatz in Leningrad, I once went to the mikva on Yekaterinislavski Canal Street with my relative R’ Chonye Morosov and he told me this story:

R’ Chonye was the Rebbe Rashab’s aide. One time, R’ Shmuel Gurary (Rashag), the wealthy Chassid and philanthropist who was mekushar to the Rebbe Rashab with all his heart, soul, and might, asked R’ Chonye to tell the Rebbe that he had arrived.

The way it worked was, the Rebbe would see R’ Shmuel Gurary in yechidus before other people, because in those terrible times of war, especially the war of the “Reds and the Whites” with the bands of Cossacks, may their names be erased, who wreaked havoc and destruction in Jewish dwellings, and much suffering was heaped upon the Jewish people and the Lubavitch yeshiva wandered from the sword of war until it went to Rostov on the River Don – Rashag was one of the closest people to Beis Rebbi and supported the yeshiva and the Rebbe’s household with counsel, money, and efforts in wide ranging communal work.

Therefore, when Rashag came, the wealthy, handsome Chassid who charmed and astonished all who saw him with his hadras panim of a genuine Chassid, one who feared G-d, whose wisdom illuminated his face – it was obvious that he would enter right away for yechidus, especially when there were tragedies and communal matters to discuss.

R’ Chonye Morosov went to the door of the Rebbe’s room to announce that Shmuel had come. How astonished he was when he had just opened the door of the room slowly and carefully and the Rebbe asked him, “Chonye, who else is waiting to come in?”

This question was astonishing to R’ Chonye because, so he told me, he had not heard a question like this ever before.

R’ Chonye enthusiastically said, “Shmuel came!” and in a softer voice he said that Shlomo Chaim the glazier had also come. To his great surprise, the Rebbe said that first Shlomo Chaim the glazier should come in.

R’ Chonye’s tongue clove to the roof of his mouth and he was stricken dumb as though the Rebbe’s words were stuck in his throat like a bone and remained stuck. He said in a hoarse voice, or more correctly, he mumbled: R’ Shlomo Chaim, go in for yechidus.

Rashag turned pale and then red and went to the room that was used as a shul and all those who saw and heard were stunned into silence by this announcement.

This Shlomo Chaim was poverty stricken and a man who suffered with sick children, a wife confined to bed with an incurable illness, unmarried daughters and a deaf son. He himself was a “T’hillim Yid.” Who was he that the Rebbe had him precede Rashag?

After a few minutes, R’ Chonye continued to tell me, Shlomo Chaim came out and Rashag went in like a wounded lion. He spent a long time in yechidus and everyone waited impatiently for when he would exit the Rebbe’s room.

R’ Chonye stood there on the street in Leningrad and excitedly described what happened next. When Rashag came out he was white like snow and plaster. “You hear,” R’ Chonye touched my shabby, old coat, “he was white like lime.”

They all surrounded him with respect and astonishment. Rashag sat down, wiped the sweat off his forehead and with a little sigh he said:

I had just walked in and stood before the Rebbe and he gently said to me: Shmuel, you learn Chassidus. Do you ever have a personal interest, an ulterior motive? You daven, are there times that you have a selfish interest? You are wealthy and generous with the yeshiva and the Chassidim, maybe here too you have some self-serving motive? You have good children, you are pedigreed, you are Shmuel Gurary – maybe in all these things there is a selfish interest or an ulterior motive?

But Shlomo Chaim is a man who suffers and one who suffers has no self-serving motives (personal enjoyment and self-awareness) and so he came in before you. That means that he, the man who suffers, is on a higher level than you, Shmuel Gurary!

R’ Chonye Morosov then remained silent until we reached the mikva.

R’ Alexander Bin-Nun (Bunin) was a member of the household of R’ Levi Yitzchok, the Rebbe’s father. After he moved to Eretz Yisroel, he settled in Raanana where he opened a school for girls with his wife.

R’ Bin-Nun is mentioned a number of times in the Rebbe’s Igros Kodesh, whether in connection with the school in Raanana or in connection to his job as supervisor of the Reshet Oholei Yosef Yitzchok schools.

As per the Rebbe’s instruction, he wrote two books and with the Rebbe’s consent he called them Toras Ha’nefesh according to Chabad. He brings excerpts from maamarim in Likkutei Torah and maamarim of the Rebbe Rayatz which mostly deal with the avodas ha’t’filla. He explains many deep concepts. Indeed, t’filla played a central role in his life as his son notes in the introduction to the second volume and as I saw with my own eyes.

How did I get to know him? In 5740 I began learning in Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim in Kfar Chabad. I still did not have Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin and when I would go visit my parents, who lived in Raanana, I was unable to stay with them on weekdays since Sunday morning I had to return to yeshiva and borrow Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin from one of the bachurim (on Shabbos too it was very hard because it was a Shmita year and I would bring fruits and vegetables from the Kfar and my mother would cook them separately for me).

My mother, who knew Mrs. Tzippora Bin-Nun, suggested that I go to them and see whether they had Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin which would solve the problem. So one day I knocked at their door and introduced myself. They were very happy and invited me in to put on Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin.

R’ Bin-Nun was old and very weak by then. He told me that he hardly ever left the house because of his heart problems, but he invited me to visit every time I was in Raanana, both to put on Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin and to visit and learn with him. I learned Tanya with him a number of times with his unique method – he did not learn it in order but according to topics and he would skip around.

He also asked me explicitly not to visit on Shabbos. I asked why and he explained that he spent the entire day davening. When I wondered how this was possible he modestly told me that in his youth he had committed not to sit while davening, for how could one sit in the presence of the King? And since it was hard for him to stand, he davened a little bit while standing and then sat down to rest and repeated that all day (the truth is that even on a weekday he also davened at great length).

THE TREASURE TROVE

Thanks to the Rabbeinu Tam t’fillin, I was able to stay in Raanana on weekdays and I was in Raanana for the summer and organized Shela (Shiurei Limud HaDas) activities for children, which was then a novelty.

It’s important to mention that no Lubavitchers lived in the entire area except for the Bin-Nun family and they continued to live there because the Rebbe told them to, even though, in every letter they wrote to the Rebbe, they asked to be allowed to move to Yerushalayim and live near their daughter.

On one of my visits, R’ Bin-Nun surprised me and gave me a collection of papers with stories and his memoirs. He included a letter to R’ Mendel Futerfas and asked me to give it all to him.

Since I saw the “treasure” that I had, I decided to first copy it all (I had no access to a copying machine) and then to give it to R’ Mendel. I’m embarrassed to say that the whole thing disappeared. I was sure it was among my papers and I looked but didn’t find them.

Then this year I moved and of course I sorted and arranged and threw things out and suddenly – there it was!

Now I ask forgiveness from these two great Chassidim and am publicizing these things as R’ Bin-Nun asked in his letter and as the Rebbe told him to do.

Yaron Dotan

R’ ALEXANDER’S LETTER TO R’ MENDEL

B”H

Tuesday in the order of B’Shalach

Motzaei Yud Shvat 5740, Shmita Year, Thirtieth Year (of the Rebbe’s nesius)

To HaRav HaTamim, Mashpia in the yeshiva of Tomchei T’mimim in Kfar Chabad, R’ Mendel Futerfas, greetings!

My great brother and friend, the notes I present to you were seen by the Rebbe and I asked the Rebbe whether I should publicize them among Anash and in yeshivos. I received an answer dated 13 Kislev 5740 which said: Many thanks, and it is a timely thing.

Therefore, I permit myself to giver over these writings to your perusal, and if and when it is fitting and desirable to publicize them among the mashpiim at farbrengens or to give them out to the students, the decision is in the hands of the Mashpia R’ Mendel.

I carry out the instructions and perhaps the advice of the Rebbe and not out of arrogance, G-d forbid, and since I have only one copy, if the notes are appropriate, print them any way you want in the desired number. If they are not suitable for those who need such things, please be so kind as to return them in two months (or even earlier) to the bachur Yaron Dotan from Raanana who occasionally learns Tanya with me.

Due to my severe heart disease, I am disconnected for two years now from Anash and have been unable to hear a single sicha from the mashpia and have not been present at any farbrengen and of course, I am greatly pained over this.

The Rebbe told me to write a compilation Toras Ha’nefesh according to Chabad, that is the name I gave it and I compiled excerpts on the topic of avoda and not haskala because my intellect is limited, for I am alone.

The compilation is, according to the Rebbe’s instructions, only from Likkutei Torah and maamarim of the Rebbe Rayatz and nothing else. Also a few maamarim from our Rebbe from the year 5718. I learn Chassidus and write and have forty pages already.

The doctors want to do open heart surgery and the Rebbe wrote, “Try to postpone open heart surgery and may Hashem grant you success.” Of course I followed this instruction of the Rebbe but to walk, speak for more than an hour – I cannot because my heart stops. I will conclude with, may I be successful with Hashem’s help and with the Rebbe’s bracha to benefit Anash with my notes and for length of days and good years.

If you can respond, that would be wonderful.

A student of Tomchei T’mimim in Russia

Alexander Zushe Bin-Nun

July 29, 2015

July 29, 2015

Reader Comments