DINNER WITH ANDRE

On the 26th of Tammuz, Mr. Andre (Mordechai) Hajdu, one of the world’s leading composers, a man who lived and breathed music, passed away at the age of eighty-four. His familiarity with and knowledge of old Chabad melodies began shortly after his emigration to Eretz Yisroel, when he heard the Alter Rebbe’s Niggun “Arba Bavos” for the first time. The life story of a conductor who was privileged to direct some of the greatest performances of Chabad music.

Translated by Michoel Leib Dobry Photos by Tomer AppelbaumNot many Chabad chassidim know that one of the most prominent niggunim in the Nicho’ach (Niggunei Chassidei Chabad) album collection is called ‘Hajdu.’ The niggun opens with this word, repeating itself over and over again, as a sign of appreciation for the devoted work of Mordechai (Andre) Hajdu, who passed away on the twenty-sixth of Tammuz. He was privileged to be an accompanist, a musical arranger, and even a composer of dozens of Chassidic melodies in the Chabad niggun project, known by its acronym: “Nicho’ach.”

Photos by Tomer AppelbaumNot many Chabad chassidim know that one of the most prominent niggunim in the Nicho’ach (Niggunei Chassidei Chabad) album collection is called ‘Hajdu.’ The niggun opens with this word, repeating itself over and over again, as a sign of appreciation for the devoted work of Mordechai (Andre) Hajdu, who passed away on the twenty-sixth of Tammuz. He was privileged to be an accompanist, a musical arranger, and even a composer of dozens of Chassidic melodies in the Chabad niggun project, known by its acronym: “Nicho’ach.”

“The mashpia, R’ Mendel Futerfas, especially loved this niggun and he would sing it at every farbrengen,” recalled Rabbi Aharon Halperin from Kfar Chabad.

Hajdu’s connection to Chabad began the year before the Six Day War, when he arrived in Eretz Yisroel and developed a close bond with the Chassidic musician Rabbi Yosef Marton. Together they worked on the Nicho’ach albums. Rabbi Marton sang while Hajdu played the piano. Hajdu ‘caught the bug,’ and even though he created and produced various kinds of music, his heart was always drawn after Chabad melodies.

Over a period of several years Hajdu performed at the Chabad evenings held on kibbutzim. Later, he even founded the ‘Kulmus Ha’nefesh’ musical ensemble at a Chabad ‘Heichal Ha’negina’ performance. His great love and affection for Chabad melodies could take expression at any time. At virtually every performance and media interview he would mention the depth of Chabad music.

Andre Hajdu was one of the most prominent musicians in Eretz Yisroel over the past several decades. He left behind numerous musical research projects, along with many students who themselves have become well-known musical performers. He was a prolific composer and his works also include numerous arrangements of Jewish music.

FROM GYPSY SONGS TO (L’HAVDIL) CHABAD NIGGUNIM

Andre, or by his Jewish name ‘Mordechai,’ a Holocaust survivor, was born in 5692 in Hungary to a secular Jewish family and studied music in Budapest. In those days, no one dreamed that this little boy who was raised in a home totally detached from Torah and mitzvah observance would eventually become a musician who passionately revived authentic Jewish melody. Hajdu started taking piano lessons when he was twelve, and shortly after he learned how to play, he began writing his own music. By the age of fourteen, he was already a well-known musician and had written an opera that received high critical acclaim.

In 5716, he moved with his mother to Paris, where he continued his studies with two prominent composers – Darius Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen. His father, Moshe, ran a branch of a large store in Hungary, and his mother, Sara, was a pianist and the owner of a photography studio. “The assimilation was so great that I didn’t think that there was a ‘Jewish People’,” Hajdu recalled in describing the days of his youth in Hungary. “While I knew that I was a member of the religion of Moshe, the only practical expression of this fact was the persecution that we suffered from our Gentile neighbors.”

During a lengthy spiritual journey searching for his heritage and arousing his intellectual curiosity, Andre slowly developed a stronger relationship with traditional Judaism, a process that only reached its culmination after his immigration to Eretz Yisroel. “I knew nothing about Jewish music at the time,” he recalled several years ago in an extensive interview he gave to a reporter with the ‘De’ot’ magazine.

“One day, at a village along the border, I met some wandering gypsies. I recorded some of their melodies and then brought them to my teacher, Zoltán Kodály, for him to hear and give his opinion. It turned out that virtually no one had dealt with the subject until then, and I became a researcher of gypsy music in Hungary. In hindsight, I now realize that my choice of gypsies was a very meaningful one: Why would a Jewish boy who went through the Holocaust choose to study gypsy music? There is something to this: the need to deal with a scattered and separate people, matters of authenticity and assimilation that were very relevant to gypsies as well.”

After he arrived in France, he continued his research of gypsy music. However, he had a hard time finding his place among the millions of foreigners and émigrés, as he was searching for his essence and some inner depth in his life. “Underneath the surface, my Jewish identity was slowly coming through. I found work in Tunis as a conservatory teacher, where I met some people with a line of thinking similar to my own, although they already had a clear Jewish identity. Until then, I had never spoken about Jewish matters even with my Jewish friends and we had never formulated anything regarding this identity of ours.”

He had already passed the first stage along his journey back to his roots, however, the truly significant encounter that brought about a meaningful change in his life was when he became familiar with the theoretical and contemplative side to traditional Judaism. This began during an exhilarating first acquaintance with the world of Torah study. At the time, he was working with a crew on a French motion picture production as the composer of the film’s score. The film’s Jewish screenwriter was then in the midst of his own kiruv process, and during his free time he would read from a small booklet. Hajdu inquired as to what this religious Jew was reading so intently.

“I’m learning Mishnayos from Tractate Bava Kamma,” the writer replied as he started reading to him: [There are] four categories of damages: the ox, the pit, the grazer, and the fire. The cadence of these ancient words captivated Hajdu, representing “the final blow” leading him to search for his inner world along the path of our holy forefathers. Slowly but surely, he returned to his Jewish roots and proudly became observant in Torah and mitzvos. “I started taking an interest in Talmud, an interest that merely grew and intensified. I felt that intellectual correctness demanded that I learn Gemara. I went to a night school in France where they taught Gemara and Rashi – and I felt that I was getting closer to my roots. Keeping mitzvos and davening only came later.”

After immigrating to Eretz Yisroel, he settled in Yerushalayim. Three years later, he met his wife Rut, and the two married and moved to the Holy City. Later, in his interview with the ‘De’ot’ magazine, he said that the main factor behind the decision to make aliya was his return to Jewish tradition.

“I knew Chabad chassidim in Eretz Yisroel and I was invited to Kfar Chabad. A month after making aliya, I was making the rounds among the yeshivos and decided to record niggunim and the sounds of Torah study even before my Hebrew was all that good. My immigrant absorption came through music and culture. Together with my research, I began working on various arrangements of Chassidic niggunim and more original personal projects, such as a combination of music and Talmud.”

ANDRE PARTICIPATING IN CHABAD MUSICAL PRODUCTIONS

A few months after his immigration to Eretz Yisroel, Andre Hajdu had already begun a collaboration with the well-known Chassidic musician, Rabbi Yosef Marton, and a warm friendship soon developed between the two. It turns out that even before Hajdu arrived in the country, Rabbi Marton had received a letter from a friend who was then serving as a representative with the Jewish Agency in France. In this correspondence, the friend told Rabbi Marton about a young gifted Jewish musician who was planning to visit Eretz Yisroel and was also considering the possibility of making aliya. He asked him to welcome and host this young man, helping him to become familiar with the Holy Land.

Within a month after his arrival in Eretz Yisroel, Rabbi Marton had invited him to spend Shabbos in Kfar Chabad at the home of the Chassidic Vocalist Rabbi Shneur Zalman Levin, of blessed memory. “I got quite a shock,” Hajdu recalled. “The Kfar and its residents made a powerful impression upon me. This was perhaps due to the fact that just fifteen miles from Tel Aviv I had found a village strikingly similar to those I remembered from Hungary – without normal roads, etc. The sight of what appeared to be Jewish peasant farmers was quite astonishing. I participated in farbrengens, as everyone said L’chaim and sang what I later learned was ‘The Niggun of Arba Bavos.’ The melody was something most unique.”

Hajdu’s connection with Chabad niggunim was deep, and it began as soon as he heard a niggun for the first time. His sharp professional sense in all things musical led him to the understanding that this was a form of music with foundations in the highest peaks of holiness. “The unique mode of Chassidic singing at farbrengens has remained with me always. Suddenly, there was opened before me a new and rich world of hundreds of Chassidic melodies, each one with a name, an explanation, and a documented history.”

As a result of this visit, Hajdu began to participate in the arrangement and production of hundreds of Chabad niggunim. Hajdu himself worked with Chabad vocalists such as Nicho’ach founder Rabbi Shmuel Zalmanov, R’ Zalman Bronstein, and R’ Zalman Levin. As a composer, Hajdu took various niggunim, and on their basis, he wrote very impressive musical compositions. His album ‘Shirim Min HaG’niza’ is based on ‘Tzama Lecha Nafshi’, the ‘Poltava Niggun’, and ‘The Shalosh Bavos.’

However, if there was one niggun that Andre feared, using his own words, it was the ‘Niggun of Arba Bavos.’ “I was afraid to make an adaption of this niggun. Even in the framework of the ‘Kulmus Ha’nefesh’ band that I established some years ago, we sing it straight, without revisions or other techniques that I use in other niggunim. This niggun contains a great deal of the Alter Rebbe’s ideological devotion, such that the audience and the performers realize that it’s best not to tinker with it.” Hajdu then added: “People who are not Chabad chassidim get an impression and an idea of Chabad through this niggun.”

Hajdu felt inspired and he immediately decided to take part in the production of Chabad music to make it more appealing to “the masses.” He quickly became an integral part of “Chabad evening” activities. He accompanied the Chassidim in their singing when they made performances, large and small. The crown jewel was running the musical side of Vols. 6-10 of the Nicho’ach Chabad recording series. Volumes 9 and 10 were none other than a well done Chabad evening with the chassidim R’ Itchke Gansburg and R’ Amram Blau. Rabbi Yosef Marton conducted the choir and leading the orchestra was Mordechai Hajdu. Rabbi Marton tells often that during the height of various d’veikus niggunim, something quite amazing would happen on the stage: The Chassidim would close their eyes and be swept up into the higher realms. Meanwhile, the orchestra wasn’t able to continue. Only one person managed to restore order: Andre Hajdu. With his skilled fingers, he would ‘go after’ the chassid, closing his eyes as well, traveling with him into the spiritual worlds… In another example among many, in the niggun ‘Der Duddlele,’ you can hear the unforgettable chassid R’ Binyomin Levin singing at an unusual tempo with Andre Hajdu accompanying him on the piano. The chassidic soul simply comes pouring out of the recording even decades later.

From the very outset, Rabbi Marton and Andre Hajdu became close friends with all their heart and soul. Once in an interview, Rabbi Marton a”h called his friend Andre “Rabbi Mordechai Hajdu,” adding that “just as he is a man of music, he is also a man of Torah and piety.”

‘THE QUILL OF THE SOUL’ SPREADING CONCEPTS OF CHABAD TEACHINGS

In recent years, together with his students, Hajdu founded the “Kulmus Ha’nefesh” (Quill of the Soul) Ensemble – a full performance devoted completely to Chabad niggunim, essentially revealing the world of Chabad music to a brand new audience. Together with performing in every possible location, he speaks with great yearning and longing about the group of Chassidim who illuminated his world and introduced him to the matchlessness of Chabad niggunim.

How did this musical development take form? It turns out that anyone who knows Hajdu would never raise such a question. Hajdu referred extensively to Chabad niggunim in the lectures and courses he gave before young students at Tel Aviv and Bar Ilan Universities. Through his teaching, he founded a band with students who were also enthralled with Chabad niggunim, and produced dozens of joint compositions. So was born the “Kulmus Ha’nefesh” Ensemble.

With a captivating smile, he recalls the group’s birth and its hundreds of riveting performances before large audiences. “One day, I introduced the niggun ‘HaNeshama Yoredes L’Toch Ha’guf,’ and from then on, everything began to develop,” he said. “We heard more niggunim and the band members connected to them in a very profound way. Then, the idea arose to put together a whole performance. Each of the players took responsibility for one niggun, and afterwards we all went over the niggun together and the arrangement was completed.”

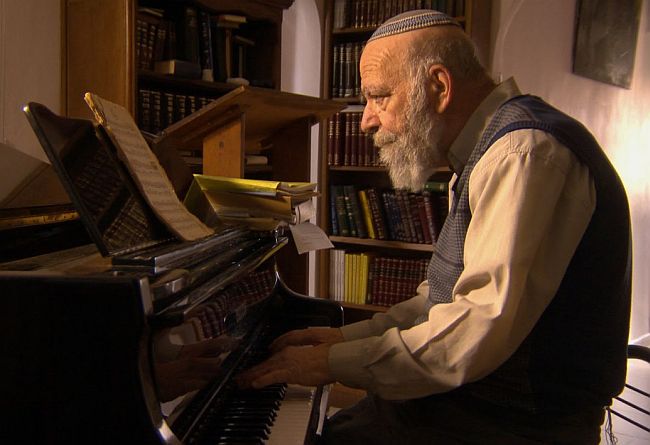

The “Kulmus Ha’nefesh” Ensemble was comprised of five musicians, a young master of ceremonies, and a white-bearded conductor wearing a large yarmulke. The musicians would stand together on the stage at the Jerusalem Khan Theatre or other musical festivals held throughout Eretz Yisroel enthralling audiences numbering in the hundreds, most of whom were not Torah observant, for an hour of original Chabad niggunim from generations past, with a never before heard musical arrangement.

On the subject of the complex work on niggunim with “Kulmus Ha’nefesh”, Hajdu recalls: “On the one hand, ‘Kulmus Ha’nefesh’ was created out of a profound sense of faith in the spirit of Chabad, getting deep into the Chabad world. This is an authentic world where we feel how it maintains a certain musical style, a way of life, and a most original musical heritage. We could have chosen another brand of Chassidism, something a bit closer to today’s experience. However, when we started working with Chabad, we immediately felt the depth of Chabad music. This authenticity is not a common thing in the music sold today under the heading ‘Chassidic music.’ Most of these albums miss the intensity of Chabad music, concentrating on the ‘schmaltz’ instead.

“On the other hand, there is a tremendous innovation in our work on these niggunim. First of all, the theatre and narrative that we put into the niggunim. We also wrote a story that we read during the performance, and between the niggunim, the audience hears the words of the Alter Rebbe on the Kabbalistic meaning behind the niggun or the voice of Rabbi Zalmanov on a recording. We don’t just sing and play music; we also try to communicate the Chabad Chassidic experience.”

A FARBRENGEN

IN THE RIGHT PLACE

The warmth of Chassidus didn’t just have an effect upon Hajdu, it also influenced his father during the later stages of his life. The spark was ignited during a farbrengen on Purim 5731, when Hajdu came with his father (who had come for a visit to Eretz Yisroel from Hungary) to Kfar Chabad at the invitation of his friend, Rabbi Yosef Marton, as Rabbi Aharon Halperin recalls. “At first, Rabbi Marton considered bringing them to a farbrengen at the home of the mashpia, Rabbi Shlomo Chaim Kesselman. However, he didn’t know that Rabbi Kesselman had not been feeling well at the time.

“When he realized that there would be no farbrengen at the Kesselman home, he asked me what I should do. I suggested that he bring them to a farbrengen taking place at our house. He followed my advice, and they came to us and enjoyed themselves very much. It goes without saying that a Purim farbrengen is something unique – the mashke flowed like water and the atmosphere was very warm.

“Hajdu’s father, Moshe, was already in his eighties at the time. He sat with us at the farbrengen saying L’chaim after L’chaim and enjoying the atmosphere immensely. I remember that he was very impressed by the Rebbe’s picture hanging in our living room. At a certain point I suggested that he put on t’fillin and he happily agreed. When he asked where he could put them on, I suggested that he go into the side room, which he did. As he rolled up his sleeve and put the t’fillin on, his eyes filled with tears.

“When he finished he told me that he hadn’t put on t’fillin for many years. He didn’t like going into the synagogue in Hungary due to its cold atmosphere. Now, during a visit to Eretz Yisroel, he was encountering a different kind of Judaism – something loving and joyous, as he remembered from his childhood before the Second World War. The chassidic warmth he discovered at the farbrengen in our home had melted his heart. He then made a resolution that he would put on t’fillin every weekday, and so he did even after he returned to Hungary until his passing a year later.”

According to his friends and acquaintances, Hajdu himself didn’t attach any importance to his musical achievements, conducting himself with great humility. A member of Yerushalayim’s Givat Mordechai neighborhood recalls: “Professor Andre Hajdu – a righteous and upright man, who always did the right thing. A sublime teacher, composer, and musician. He had an exceptional personality. His musical activities were abundant and greatly respected, heard in every country.

“He would be in shuls and battei midrash, mornings and evenings, for prayer services and Torah classes. He would often go to the synagogues of different ethnic groups, especially the Yemenite shul in Yerushalayim’s Givat Mordechai neighborhood.”

During the last decade, Hajdu would regularly participate in Chassidic farbrengens on auspicious days of the Chabad calendar with the members of the “Kulmus Ha’nefesh” band, singing together with great fervor and devotion. He always spoke with much appreciation for Chabad music, particularly for Chassidim and people of action whom he came to know and later gave him valuable guidance along the path to greater Torah observance. At one recent farbrengen in Kfar Chabad he performed together with his band and the musicians tremendously enjoyed the direct contact with Chabad Chassidim.

Andre Hajdu was eighty-four years old at the time of his passing, leaving behind a wife and six children. His legacy includes his musical compositions, his musical research projects, along with many students who themselves have become well-known musical performers. There can be no doubt that the world of Chabad music owes him a great debt of gratitude.

November 2, 2016

November 2, 2016

Reader Comments