A TOWER OF CHASSIDIC STRENGTH

Whoever knew the Chassid, R’ Chaim Shneur Zalman Kozliner, known by the acronym “Chazak,” knows that he was a different sort of Chassid. He was strong, like his nickname, a courageous Chassid who was afraid of no one. Despite the suffering and torture he endured the two times he was arrested, he continued to live a Chassidic life and spread Torah everywhere. * From his childhood in the Chassidic town of Disna and his learning in Lubavitch, to his working as a secretary for the Rebbe Rayatz, and then imprisonment and exile to Siberia, the image of a Chassid.* To mark his passing on 13 Tishrei.

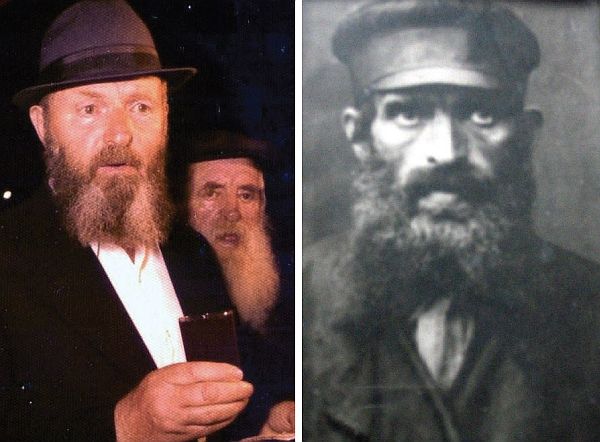

Brothers – on the right, R’ Chaim Zalman and on the left R’ Efraim Kozliner | R’ Boruch Yosef Kozliner of DisnaCHASSIDISHE ROLE MODEL

Brothers – on the right, R’ Chaim Zalman and on the left R’ Efraim Kozliner | R’ Boruch Yosef Kozliner of DisnaCHASSIDISHE ROLE MODEL

R’ Chaim Shneur Zalman Kozliner, known as Chazak, was born in 5661/1901 in Disna in White Russia. His father, R’ Boruch Yosef, was a teacher of Torah to young students. They said about him that when his students got older, they were the best students in Tomchei T’mimim in Lubavitch.

When Chazak was small, the mashpia, R’ Yisroel Noach Blinitzky lived in his parents’ home. He saw and absorbed from R’ Yisroel Noach what a Chassid is, and how he behaves.

Why did R’ Yisroel Noach live with the Kozliner family? He had married Sterna, daughter of R’ Itche Yaffe, who lived in Disna. After they married, the couple wanted to live in Disna near her parents, but they did not have money to buy or even rent a house. So R’ Boruch Yosef came to their aid. He was a dear friend of the kalla’s father and was willing to host the couple for several years for free.

So aside from the Chassidishe chinuch that R’ Chaim Zalman received from his father, R’ Yisroel Noach provided him with a role model of a Tamim from Lubavitch.

Disna in those days was called a “town of Chassidim” since all its residents were Lubavitcher Chassidim. Although they did not all conduct themselves punctiliously in all the Chassidishe minhagim, when it came to a Chassidishe farbrengen, they all participated with Chassidishe warmth and enthusiasm.

In those days, R’ Itche Disner became sick with typhus and he died shortly thereafter. The doctors forbade burying him in fear that all those who handled the burial would contract the disease. The family was beside itself. They could not make peace with the fact that their father would be buried in one large communal grave with others who died of typhus, Jews and gentiles.

Once again, the family friend, R’ Boruch Yosef, came to their aid. He could not accept that his good friend would not be given a Jewish burial. What he did was drink a large cup of vodka. When he finished he said, “Now I’m clean (i.e. sterile). Typhus won’t harm me.”

He then buried his friend and miraculously did not contract typhus.

I GAVE YOU TO TOMCHEI T’MIMIM

At the age of nine, Chaim Zalman went with his father to Lubavitch where he attended the local elementary school. When he got a bit older, he entered Tomchei T’mimim under the direct leadership of the Rebbe Rashab. His brother Efraim was there too. His good friends in yeshiva later became famous Chassidic figures such as R’ Zalman Shimon Dworkin, later rav of Crown Heights, the mashpia R’ Nissan Nemanov, R’ Sholom Posner and others. These true friendships continued throughout the years.

Now and then, his father would visit the yeshiva where he met with the maggidei shiurim and the mashpiim and had long conversations with them. Chaim Zalman was very curious to know whether his father was asking them about him. He asked one of the mashpiim whether his father was inquiring about his diligence in learning or his Chassidic behavior. To his great surprise, the mashpia said, “Your father never asked me about you.”

Chaim Zalman went over to his father who was still in the yeshiva and asked him why, as his father, he did not inquire about him. R’ Boruch Yosef replied, also in surprise, “I gave you over to Tomchei T’mimim. Do I need to ask about you? I rely on the hanhala of Tomchei T’mimim that they are educating you properly.”

Indeed, R’ Chaim Zalman was considered a lamdan among the talmidim of the yeshiva. His friends said that he was gifted with an eizene kup (head of iron).

THE REBBE’S SECRETARY

With the Communist Revolution of 5677/1917, the yeshiva had to leave Lubavitch and wander among various towns. R’ Chaim Zalman wandered together with the rest of the talmidim.

In Tishrei 5684/1923, the Rebbe Rayatz sent word that he wanted the T’mimim to return from their places of study to Rostov where the yeshiva was reestablished.

|

H |

e could not accept that his good friend would not be given a Jewish burial. What he did was drink a large cup of vodka. When he finished he said, “Now I’m clean. Typhus won’t harm me.” He then buried his friend and miraculously did not contract typhus.

R’ Chaim Zalman merited an unusual kiruv when, even as a bachur, he served for a brief while as the Rebbe’s secretary when he lived in Leningrad. His main task was responsibility for the monies of Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim. R’ Chaim Zalman, who was by his very nature a closed-mouthed person, never spoke about the time he shared an office with the Rebbe Rayatz, but Chassidim related some episodes from those days.

While sitting there with the Rebbe, they usually did not speak, because “the walls have ears.” Their communication was mainly with their eyes; hints from the Rebbe sufficed for him to know what to do. The great care and secretiveness of that era was necessitated by the reality of the times.

However, it once happened that they discussed an important topic and R’ Chaim Zalman expressed his opinion and the Rebbe said his, and thus began an analytic discussion of the views which were expressed. Suddenly, the Rebbe looked up and gazed at R’ Chaim Zalman who became silent. It was a moment when he realized that the subject was no longer up for discussion and that he had to obey with kabbalas ol.

One time, he took the opportunity and complained to the Rebbe that his gentile neighbor was making his life miserable. The Rebbe gave a short, sharp response, quoting the verse, “his spirit will depart, he will return to the earth.”

R’ Chaim Zalman, who understood what this meant, ran home in order to tell the neighbor that he’d be better off asking forgiveness before his life ended, but when he got home, wailing could already be heard from the neighbor’s house.

HE LEFT IN THE MIDDLE OF HIS SHEVA BRACHOS

Tuesday night, 15 Sivan 5687/1927, the police knocked at the door of the Rebbe Rayatz and after a protracted search, they arrested him. This was the beginning of the famous and terrible arrest.

R’ Chaim Zalman happened not to be in the area at the time, for he had married his wife Tzippa, daughter of R’ Chaim Elozor Garelik, a few days before. The wedding took place in Rogatchov, where the kalla lived, and R’ Chaim Zalman was in the midst of the week of sheva brachos when it happened.

R’ Chaim Zalman was quickly called by the leading Chassidim to return to Leningrad in order to help get the Rebbe released. R’ Chaim Zalman did not delay.

By orders of the Rebbe Rayatz, he was entrusted with the “black notebook,” as he called it. This notebook contained a list of rabbanim, maggidei shiurim, mashpiim, melamdim, and mikva ladies in every city of the Soviet Union.

News of the Rebbe’s arrest spread quickly among the Chassidim of the Soviet Union, but time elapsed before the news also went beyond the Iron Curtain and reached the Chabad Chassidim in America. Nobody dared to write a letter abroad, especially not on such a sensitive matter, something which could have cost the life of the letter writer. The first who dared to write to the US was his father, R’ Boruch Yosef Kozliner, who was willing to endanger his life to save the Rebbe.

Although R’ Chaim Zalman knew that the secret police were nipping at his heels, he continued to work to maintain the yeshivos. He moved to Nevel where he joined the hanhala of the yeshiva and the beis midrash for rabbanim and shochtim. Together with him were other venerable Chassidim: R’ Shmuel Levitin, R’ Nissan Nemanov, R’ Yehuda Eber and R’ Zalman Alpert.

Dozens of bachurim studied sh’chita and rabbanus and after being ordained for these roles they were sent to various cities throughout the Soviet Union to help the communities which were destroyed by the Yevsektzia (Jewish communists).

In the yeshiva’s good days, about eighty T’mimim learned there, and these years were “like a microcosm of Lubavitch” as R’ Yehuda Eber, the rosh yeshiva, later said, referring to the days when the yeshiva was in Lubavitch.

The Yevsektzia did not leave the yeshiva alone and the hanhala and the students suffered from persecution until Kislev 5689 when the yeshiva was closed down. R’ Shmuel Levitin, the top administrator, was arrested and the other administration and staff members went into hiding, as is described in Yahadus B’Russia HaSovietis:

“In Kislev 5689 some bachurim were arrested and vigorous searches were conducted to try to find the members of the staff. Some shuls where the bachurim had been learning were closed even to those who davened there. The one who was in charge of this work was a Jew named Altshuler. He did not rest with his work of destruction. The yeshiva would have been completely destroyed if not for G-d’s kindness that the administrative staff managed to hide somewhere, and from their place of hiding they gave orders to the talmidim to leave Nevel.

“Groups scattered to a number of cities. One group went to Leningrad, led by R’ Nissan Nemanov, another group to Vitebsk, led by R’ Avrohom Drizin, and a group went to Yekaterinoslav.”

Everything that was done was reported to the Rebbe Rayatz, and he wrote about this in a letter dated 2 Shevat 5689, “Surely they have read about all that was done with the hanhala of the yeshiva in Nevel and the hanhala of the beis midrash for rabbanim and shochtim, may Hashem have mercy and may they soon go out in freedom. But thank G-d, in their stead there are now serving other appointees who are involved with the talmidim, many of whom traveled to other places.”

THE SENSIBILITIES OF A THREE YEAR OLD

The persecution of R’ Chaim Zalman continued and increased, especially since he was one of the directors of the yeshiva. The secret police tightened the noose around him. It was at this time that his oldest child Mordechai was born, on Acharon shel Pesach 1929. Shortly thereafter, the new father had to flee the city.

A month after the birth, Tzippa began to worry because it was time for a pidyon ha’ben, but her husband, whose mitzva it was, had disappeared. Not long after, she received a coded telegram from him which said, “Mazal tov on the purchase.” She understood that her husband had remembered the rare mitzva and had redeemed his son from his place of hiding.

Some time later, R’ Chaim Zalman returned home but the persecution and searches continued. In the home there was a constant feeling of underground activity and being on the run, so that three year old Mottel already knew how to behave in troubled times.

One day, the police entered his home and began conducting a search. Mottel sat down on a suitcase which contained documents. These documents contained incriminating material that, were they to be found, would place his parents in grave danger. The police did not suspect a little boy, who was innocently sitting on an old suitcase and playing, of concealing anything.

That is how, with Hashem’s kindness, and thanks to a little boy who grew up to become a mashpia, his father was saved.

A few years later, R’ Chaim Zalman moved to Shchyolkovo, a suburb of Moscow. Here too the fears did not subside and arrests were conducted now and then among the Chassidim.

One night, his fear was realized. There was pounding at the door and in walked men in black coats who brandished red certificates of the NKVD. They informed R’ Chaim Zalman that he was under arrest and took him away.

During the interrogations he realized that they knew his full name, Chaim Shneur Zalman Kozliner and not the shortened form, Chaim Zalman. It turned out that they had been looking for a “Chaim Zalman” (that’s what it said on all the letters and documents of Tomchei T’mimim) but they hadn’t managed to figure out who this man was.

(In a similar vein, they say that one time policemen went to his house and asked him where is Chazak. He replied that his name was Chaim Zalman Kozliner and that Chazak lived nearby. He went outside with the policemen and showed them the way to Chazak’s house… The policemen left and he took his tallis and t’fillin and fled out the window for he figured they would soon realize they had been duped.)

After lengthy interrogations, suffering, and torture in the cellars of the NKVD, he was sentenced to exile in Siberia. After a long, exhausting journey he arrived at a labor camp where he spent a long time together with his friend, the mashpia, R’ Nissan Nemanov.

As was his way, he also kept this part of his life to himself, so not much is known about the interrogations and imprisonment.

When he returned home, his family members sensed that something was bothering him. When he was asked, he said he was troubled by having been contaminated by forbidden foods and he explained:

The prisoners in the labor camp worked primarily on chopping down trees. The work was backbreaking and dangerous. At the end of a day’s work each prisoner received a small portion of bread and treif soup. He and R’ Nissan would pour out the treif soup and would suffice with bread and water but the Jewish prisoners who they became friendly with begged for their soup. The two Chassidim knew that the hot soup was something the prisoners were halachically allowed to eat because they were engaged in hard labor in bitter cold conditions. Still, how could they knowingly give a Jew treif food to eat?

R’ Nissan just could not give treif food to these Jews while R’ Chaim Zalman could not withstand their pleas and decided that since it was pikuach nefesh he could give them the soup and save their lives. Every day, he gave them his soup and told them, “Just eat the soup, but don’t gnaw on the bones.”

Nevertheless, this bothered him more than all the suffering he had endured in the interrogations and the exile in Siberia. He felt as though he himself had eaten treif.

Even after both of them were freed from the labor camp in Siberia, the danger of another arrest was still a possibility. R’ Nissan hid in the home of his good friend, R’ Chaim Zalman. They provided him with a hidden room and every knock at the door sent R’ Nissan back to his hiding place which the family called “the freezer” since it had no heat and during the winter was freezing cold.

The good friendship between these two Chassidim led their friends to say about them, “R’ Chaim Zalman and R’ Nissan are one body and one soul.”

RESCUE MIRACLE

In 5701, the Nazis invaded Russia and the great flight began. The residents of Russia tried to escape from wherever the German army was approaching. Civilians, especially Jews, fled to distant parts. Chabad Chassidim fled mostly to Central Asian cities like Tashkent and Samarkand.

At that time, R’ Chaim Zalman and his wife had three children, Mottel who was 12, Dreishke (Levin) who was 8, and Devorah (Vera Boroshanski) who was 3. The Kozliner family packed their meager belongings and left by train with other family members for distant Uzbekistan.

The train was packed with passengers and the terrible crowding made for suffocating conditions. Contagious diseases felled many of them. Many could not take the travails of the journey and died on the way.

Mottel and his two year old cousin Faiga Katzenelenbogen became seriously sick. There was no medicine and it wasn’t possible to rest on the train. The family constantly prayed that the children would survive at least until they arrived someplace civilized where a local doctor could treat them properly.

R’ Mottel became better but Faiga was still in serious condition. Having no choice, her parents, Shimon and Mussia, got off the train with her and hospitalized her in Tashkent while the rest of the passengers, including the Kozliners, continued to Samarkand. Faiga miraculously recovered.

The refugees suffered from starvation and disease. The Chassidim who were already in the city did a lot to help the newcomers who were streaming into the city, lacking everything. They provided for both material and spiritual needs. A branch of Tomchei T’mimim was opened in Samarkand where distinguished Chassidim, including R’ Chaim Zalman, taught the students Nigleh and Chassidus.

R’ Berish Rosenberg was someone who became involved with Lubavitch at that time, thanks to those Chassidim. He got to know the Chassidim and their way of life and became attached to the ways and teachings of Chassidus. R’ Chaim Zalman was greatly mekarev him and would disclose to him where the farbrengens were taking place. In those days, the location of farbrengens was a secret but R’ Chaim Zalman, who knew that R’ Berish was very interested in Chabad, always told him.

The relationship between the two continued for many more years. Their friendship was so strong that when R’ Berish passed away, they did not tell R’ Chaim Zalman.

During the war years, the government drafted all men. They searched after those trying to escape being drafted and arrests were a daily occurrence. R’ Chaim Zalman himself was avoiding the draft. Whenever soldiers came to the house, he managed to hide. One time, soldiers knocked and R’ Chaim Zalman realized it was too late for him to escape, but his daughters saved him. They took the mattress off the bed, he laid down on it, and they put the mattress and blankets on top of him and quickly made the bed again. The soldiers searched for him unsuccessfully and left without him.

During the war, his mother Rochel Miriam was killed by the Nazis as well as his brothers and sisters in Disna. His father died a few years before the war.

THE FAMILY DISPERSES

At the end of the war there was an opportunity to escape the Soviet Union. Many Chassidim left with forged Polish papers. Like many other Chassidim, R’ Chaim Zalman went to Lvov for the purpose of trying to cross the border. Here is where his and his family’s mesirus nefesh and courage came to the fore. His wife and some relatives worked very hard to help as many Chassidim as possible leave Russia. They helped forge documents and with the organizational aspects of the escape. Although they could have crossed the border themselves early on, they decided to remain in Lvov to help others and only then escape themselves.

His brother-in-law, R’ Mendel Garelik, who was artistic, forged the passports. Tzippa would then go to the OVIR emigration offices to get the passports signed with the stamp that allowed Polish citizens to leave the country. She had dozens of forged documents on her. Whenever she visited those offices she knew that she was endangering herself, for whoever was caught smuggling across the border was exiled for years and some were even shot.

It was Friday afternoon, 28 Cheshvan 5707. Tzippa was on her way to the OVIR office. She was holding a small bag which contained dozens of passports. On the way, she realized she was being followed. She immediately ran to the public bathrooms so she could get rid of her bag, but she didn’t make it. The NKVD agent ran after her and caught her. She pulled Tzippa toward a waiting car.

While under arrest she was tortured but she did not reveal anything since she did not want to incriminate other Chassidim.

The next day, Shabbos morning, the secret police made wide-ranging searches, entered the homes of Chassidim and made arrests. When they reached the Kozliner home, Mottel opened the door. He told them he did not know where his father was. R’ Chaim Zalman had fled. Surprisingly, they decided to arrest Mottel, who was just 18 years old, in an attempt to get incriminating information from him against his parents.

Mottel was interrogated for hours. They told him that they knew that Jews going to Poland were not Polish citizens and that they were continuing on to other countries. They also “informed” him that his mother was arrested and they had found the passports on her of those who sought to escape.

Mottel was released toward the end of the day. It was now his responsibility to care for his two younger sisters, since his mother was in prison and his father had disappeared into hiding.

|

H |

e complained to the Rebbe that his gentile neighbor was making his life miserable. The Rebbe gave a short, sharp response, quoting the verse, “his spirit will depart, he will return to the earth.” R’ Chaim Zalman ran home in order to tell the neighbor that he’d be better off asking forgiveness before his life ended, but when he got home, wailing could already be heard from the neighbor’s house.

Tzippa was sentenced to ten years of exile. That was a light sentence, relatively speaking (see box), as many others were sent to exile for decades and others were even killed for crimes like this.

Life at the Kozliner home was terrible. Their parents were gone. Mottel tried to live below the radar most of the time. His sister Dreishke was sent to Lvov where she stayed with a local family so she could be near her mother and bring her food packages. The younger sister Vera was passed around among Chassidishe families that were willing to have her. She spent a significant amount of time with the Lebenhartz family. Her hosts, who knew where her father was hiding, brought him to their home once every few months so he could see his daughter. He would come in the middle of the night, talk with his little girl and then go back into hiding.

ARREST AND TORTURE

Tzippa was released from a labor camp early, after about three years. Her joy was not long-lived for a few weeks later, the evil ones laid hands on her husband. He had sensed that trouble was approaching and he had consulted with his family about whether it was better to run away or to turn himself in and take all the blame in order to exonerate others. In the end, he decided to flee, maybe Hashem would have mercy and he would be saved.

The secret police continued to follow him. They did not arrest him because they wanted to see with whom he met. The wicked ones chose “to play the game with him” until the end.

One day, as he walked down the street, a policeman approached him and asked him for his passport. R’ Chaim Zalman innocently handed him his passport. The policeman eyed it briefly and then put it in his pocket and began walking away. The point was to hobble him, for with his passport in their possession, he could not escape anywhere.

He realized what was going on and worked to get a new passport. The forgers among the Chassidim asked him whether he wanted his real information on it or not. He said they should enter the real details.

Not much time elapsed and he was caught again, this time with his forged documents. When they accused him of being in possession of forged documents, he said, “You took my passport and since I couldn’t go around without one, I had to make another one.”

It was years later that he revealed a little bit of the time he was arrested:

“When I entered the prison, I determined not to break and not to give them the name of a single Jew. I planned that if I felt I was going to break, I would make believe that I was revealing information but only give them made up details. As expected, they tortured me severely but in my mind I was like a dead man; no wife, no children, no life on the outside and no suffering; nothing interested me. That is how I survived.

“The torture intensified. They placed a branding iron on my shoulder and forced me to crouch with it, no chair beneath me, for days, with a jailer standing nearby. I knew that if I did not do as they ordered, he would beat me. The suffering was tremendous but I did not break.

“Three weeks had passed since I was incarcerated. One night, at four in the morning, I informed them that I was willing to reveal the secret about who forged my passport. They immediately convened all the interrogators. They brought me into the interrogation room where there was a festive atmosphere. Everyone smiled. Kozliner had broken. He was going to tell everything.

“But I did not consider telling any of the truth, G-d forbid. While I was in jail, I remembered an old Jewish man who had married a gentile and had recently died. I decided to blame him for he had already died and wouldn’t be harmed. I said there was an old Jew who was an expert forger and he took care of my documents in exchange for a lot of money.

“They bought the story and went to search his house. After I left prison, I heard that they had turned the house over, but did not find anything. His gentile wife cursed her husband for having fooled her. For all those years she had thought he was an avowed communist and now she was told he had forged documents and was an enemy of the state. They searched his house, found nothing and were sure he had managed to destroy or hide all evidence of his forging.”

R’ Chaim Zalman was exiled to Siberia again where he did hard labor. Despite the circumstances, he kept mitzvos with tremendous mesirus nefesh.

The evil Stalin died in 5713/1953 and the oppression let up somewhat. Many political and religious prisoners were freed early including R’ Chaim Zalman Kozliner.

A BEARD AT ALL COSTS

After he was released, he lived with his family in Chernovitz. The mashpia, R’ Mendel Futerfas lived with them for a while. When the younger daughter, Vera, got married and moved to Samarkand, near her in-laws, R’ Mendel convinced him to move near one of his children. R’ Chaim Zalman agreed and moved to his daughter’s house in Samarkand. A short time later, R’ Mendel also went to Samarkand and R’ Chaim Zalman, his daughter and son-in-law, hosted him in their home for a long time.

Throughout the years, R’ Chaim Zalman had a beard even though this endangered him. When he was not in hiding, he farbrenged with the Chassidim a lot and encouraged them to continue working according to the instructions of the Rebbeim, despite the enormous obstacles.

A MAN OF FEW WORDS

He received a visa at the beginning of the 1970’s and made aliya with his family and settled in Nachalat Har Chabad. In 5737, when the Rebbe urged that mashpiim be appointed in every community, the residents of Nachalat Har Chabad wanted to appoint him as the mashpia but he refused. Even when the pressure increased, he adamantly refused. Finally, his brother-in-law, R’ Sholom Vilenkin, and R’ Michoel Mishulovin were appointed as mashpiim.

R’ Chaim Zalman was a happy, modest and closed-mouthed Chassid. When he visited 770, he refused his friends’ request that he sit together with the elder Chassidim and mashpiim who sat behind the Rebbe. He said, “I cannot sit within the Rebbe’s four cubits.”

R’ Chaim Zalman was an extremely taciturn man. Only rarely did he tell about his life. When his children and grandchildren asked him questions, he answered briefly and obliquely. His family knew that to him, his past was behind a sealed wall. Even the little that they knew about his activities was learned from his friends in Russia and not from him.

This is why, what has been related here is only a drop in the bucket of the life and times of R’ Chaim Zalman.

He passed away on 13 Tishrei 5746, on the yahrtzait of the Rebbe Maharash. Incredibly, his father and wife had also died on the same date.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

MRS TZIPPA KOZLINER

Mrs. Kozliner was a fearless woman who was not afraid of the police. She was very involved in various important matters.

As related in the article, after she was arrested, she faced a severe sentence since she was accused of being a traitor to the state. As one of the organizers of the mass escape from Russia, the government wanted to sentence her to twenty-five years in Siberia, or worse.

Upon her arrest, the Chassidim who had left the country thanks to her efforts felt obligated to do something to have her released. Some Chassidim repeatedly asked the Rebbe Rayatz for a bracha but the Rebbe remained silent. It was only after more importuning that the Rebbe gave a blessing that she should quickly leave prison.

Indeed, the unbelievable happened. Her trial took place in Lvov, and it was clearly a prearranged show trial. She wasn’t even brought to the courtroom. A troika sentenced her to only ten years imprisonment.

It seemed obvious that she would be sent to Siberia where political prisoners were usually sent, but that is not what happened. From the prison in Lvov she was transferred to a way-station from where prisoners were sent to their places of exile. Here is where she first met with her family. They found it hard to recognize her. They were shocked to see her suffering from swelling all over her body.

For no apparent reason, she was sent to a labor camp near Lvov where she worked in a bulb factory. The location, in the center of Russia, was a great lightening of her sentence.

There were also dangerous criminals that were sent to this labor camp. She later told that at her last meeting, before being sent to the camp, she was given a package of kosher food by her daughters. But her cellmates wanted it and the first night, as she lay in bed, she heard the prisoners talking among themselves: let’s kill the Zhidovka (derogatory word for Jewess) and take her package. She got out of bed and gave the package to them and said she did not like the food they had sent her from home. That’s how her life was saved.

Her daughters, who were very concerned about her, asked their aunt, Mussia Katzenelenbogen, to try and get her sister released early. Mrs. Katzenelenbogen told about these efforts in So’arot B’Dmama:

“One day, my sister Tzippa’s daughters came to me and asked me to save her. I dropped my work and planned for a long trip. Before I took action, I received brachos from three Chassidim, including R’ Berke Chein. I could not wait for the Rebbe’s answer due to lack of time and the urgency of the matter.

“Tzippa suffered from heart trouble and was hospitalized in the camp’s main infirmary. I went to Lvov where I met her at the camp. She said the doctor was Jewish and he could be spoken to about her release. When I spoke to him, he maintained that she was a political prisoner and could not be released. He offered to try and get her another trial. For that I traveled to Kiev where they told me that the opinions of three doctors were needed who would say that she is sick and only then could she have another trial. I expended much effort until I was able to convince three doctors to sign off on her supposed sickness.

“During this period, I visited her in the camp several times. The last time we met she asked me not to come again because the commanders of the camp looked askance at this. ‘I am afraid they will arrest you too,’ she explained.

“At precisely that time, an opportunity arose to shorten the sentence. It was after one of the inmates had murdered someone. A special committee arrived which served as a sort of court, in order to sentence the murderer. It was rare for judges to go to a labor camp. The doctor who decided to help Tzippa exaggerated her condition and sent her file to the judges along with a recommendation that she be released as a dangerously ill person.

“The efforts bore fruit and her doctors soon informed her of her release. She was freed in 1949, two years and eight months after they had sentenced her to ten years incarceration. As the Rebbe Rayatz had predicted, she would not have to be there for long.

“She was released on Tisha B’Av 5709. The two of us happily boarded a train but then the camp commander asked his men to search for me. He wanted to take revenge on me for having successfully released Tzippa. He boarded the train and looked for me in all the compartments but I lay there with eyes closed and a different kerchief so he couldn’t identify me. It was only when the train began moving that I could breathe a sigh of relief. I thanked G-d for the big miracles He did for us.”

September 24, 2015

September 24, 2015

Reader Comments