R’ Shraga Elimelech (Meilich) Kaplan went to Tomchei T’mimim and became one of the diligent talmidim there. * For many years he was persecuted because he spread Torah and he was even arrested several times. He finally left Russia for Eretz Yisroel where he was appointed maggid shiur in the new Tomchei T’mimim in Lud and the rav of the Chabad community there. * Part 2 of 2

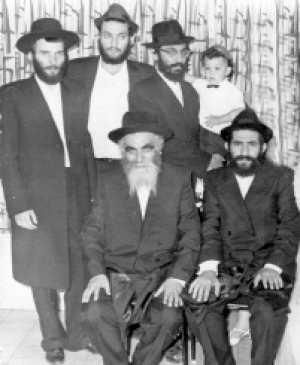

Sitting: R’ Meilich and his son Boruch. Standing from right to left: his son Nachum (with his child, Yosef Yitzchok), his son Leibel, his son-in-law Moshe YudelewitzAs was told in the previous chapter, some T’mimim joined a group of Jews who arranged with a professional smuggler to take them over the border to Turkey. The smuggler waited for them but together with him were NKVD agents who arrested them all. The group knew that they now faced the death penalty.

Sitting: R’ Meilich and his son Boruch. Standing from right to left: his son Nachum (with his child, Yosef Yitzchok), his son Leibel, his son-in-law Moshe YudelewitzAs was told in the previous chapter, some T’mimim joined a group of Jews who arranged with a professional smuggler to take them over the border to Turkey. The smuggler waited for them but together with him were NKVD agents who arrested them all. The group knew that they now faced the death penalty.

About two weeks after their arrest, one of the members of the hanhala of the network of yeshivos Tomchei T’mimim in the Soviet Union wrote a report to the Rebbe Rayatz who was in Riga. In his report are the names of the bachurim who were in the network of yeshivos and where they were located. In the paragraph entitled tefisa (lit. grasp, synonym for jail) was written the names of the boys in this group: Michel Patchin, Michel Piekarski (who lived in New York for many years), Elimelech Kaplan, Zalman Levitin (he was the menahel and mashgiach of Tomchei T’mimim in Kutais in Georgia), Yitzchok Lippman, Shlomo Matusof (shliach in Morocco, a”h), Abba Levin, and two boys from Bukhara – Mendel and Yochai (their last name was not known to the person writing the list).

“Apparently, all these are studying in Batum in tefisa, may Hashem protect them. Apparently, also in the group is the son of the Masmid (meaning R’ Eliezer, the son of R’ Itche der Masmid who was in the group), and the two rabbanim – R’ Avrohom Levi Slavin and R’ Mordechai Perlov.”

Their situation was not known to their families at first. R’ Meilich’s father, R’ Aryeh Leib, asked the Rebbe Rayatz to get involved but the Rebbe replied: “As of now, nothing is known about their situation and it would be difficult to do anything.” A few days later additional details became known and the Rebbe wrote about this to one of the Chassidim, “As was clarified, they are in prison in Batum and their situation is very difficult and entails danger to life, G-d forbid.” Then various possibilities were written about how to try to help them.

R’ Meilich suffered greatly in jail as his son R’ Nachum related:

“When he was brought to prison and put in a cell, the veteran prisoners immediately went over to him and boldly removed his yarmulke. He later said that he knew that he could not display anger, for then the inmates would bother him even more, so he remained quiet. It was only when he saw that they weren’t noticing that he took the yarmulke and put it back on. A short while later they removed it again and he kept quiet. This happened a number of times until they stopped.

“He received a package from home with food. He gave all the food to the leader of the inmates and from then on, the attitude toward him changed dramatically. My father knew how to manage in every situation.”

The youngest prisoner of all was R’ Shlomo Matusof and this is how he described the imprisonment in his memoirs:

“I sat there for three months until the conclusion of the interrogations of all the accused and their court cases for the crime of smuggling across the border which was against the law… We spent Pesach in jail. Representatives from the prisoners’ families came, as well as Georgian Jews, and supplied us with some holiday items… When all the interrogations were finished, they released some women who came from Bukhara and me too, because of my age. I was only 16 and not eligible for sentencing. The older prisoners remained in jail until their sentence was announced – three years in exile.”

Under the circumstances, exile did not mean Siberia but labor camps in the area. R’ Perlov was sent to Tbilisi in Georgia and R’ Eliezer Horowitz was sent to Tashkent in Uzbekistan.

R’ ITCHE DER MASMID MEETS THE SOVIET FOREIGN MINISTER

While they were in prison, international efforts were made to free them. R’ Shmuel Kosovitzky, R’ Meilich’s uncle, who lived in London, told the story to reporters in London and as a result, newspapers around the world began making a commotion about the injustice being done to innocent citizens who wanted to leave the Soviet Union and how people were arrested through a provocateur.

The head of the secret police was asked by Jewish figures from around the world to release the prisoners. In the end, these efforts were successful, in no small part thanks to R’ Itche der Masmid whose son was one of those arrested.

In those days, there were no diplomatic ties between the United States and the Soviet Union, and Russia very much wanted these ties. At precisely this time, the Russian foreign minister, Litvinov (who was a Jew) paid a visit to the US in order to try and arrange diplomatic ties.

R’ Itche Masmid was in the US at that time on shlichus for the Rebbe Rayatz and he was able to arrange a meeting with Litvinov with the aid of one of the senators. At the meeting, he told him about the group who were arrested because the people wanted to cross the border and that his son Lazer (later the mashgiach in Tomchei T’mimim in Lud) was arrested along with the group.

The foreign minister did not feel comfortable in front of the Americans about having a group of young people sitting in jail because they wanted to leave the country. He immediately used his influence which led to their release within a short time.

ARRESTED AFTER

BAKING MATZOS

When R’ Meilich left jail, he went to Kiev where his father was the rav and the rosh yeshiva of the local Tomchei T’mimim. R’ Meilich learned in this yeshiva together with R’ Meir Itkin, R’ Nachum Volosov, R’ Yisroel Yehuda Levin, and others.

A few months had passed since their release and once again he was arrested, this time for baking matzos. It was before Pesach, and somehow his father had obtained some shmura wheat from Haditch in the hopes of baking matzos that would suffice, barely, not only for his own family but also for the Jews of the city.

One of the members of the Jewish community who managed a mill for materials that were used as fillers in manufacturing cement, offered R’ Kaplan the use of the mill to grind the wheat. He made this illegal act conditional on their doing it under cover of darkness. He knew that if he was caught he would be subject to a severe punishment. R’ Kaplan agreed and late one night he sent his two sons, R’ Meilich and R’ Moshe Binyamin, to the mill. The two of them worked a long time cleaning parts of the mill and then they prepared to grind the wheat for matza. They finished their work late at night and walked home with a sack of flour on R’ Moshe Binyamin’s shoulder.

The street was pitch black and they did not notice a policeman standing on the other end of the street. When they finally saw him it was too late. He demanded to see their ID’s. R’ Moshe Binyamin showed his ID, but R’ Meilich did not have any, so he was arrested and sent to the police station. R’ Moshe Binyamin returned home alone and R’ Meilich’s family were beside themselves. He had just been arrested a few months earlier and now he was in jail again. It was a small consolation that the policeman did not check the contents of the sack and at least the Jews of the city had the flour.

The chief of police in Kiev was a particularly cruel man and a virulent anti-Semite. So although he knew that R’ Meilich was a legal resident and had committed no crime, he sent him to the Lukyanivska prison to await his sentence there.

R’ Meilich’s worried father consulted with a lawyer who advised him to meet with the president of the Ukraine (in those days, the Ukraine was a republic of the Soviet Union and had its own local government), a Mr. Petrovsky, who was known as a nice man.

R’ Kaplan immediately went to Charkov where the president lived. Every morning, he stood at Petrovsky’s door in the hopes of meeting him. In the meantime, the Jewish community in Charkov used its connections in government circles and a meeting with the president was arranged.

Petrovsky listened to R’ Kaplan in a welcoming manner. R’ Kaplan explained how his son was sickly and weak and could not survive incarceration or exile. His words fell on receptive ears. The president decided to allow the prisoner to remain under arrest in Kiev and then would pardon him because of his weak, sickly state.

But this is not what happened. R’ Meilich was categorized as an illegal yeshiva student who never worked and this complicated matters. It was necessary to obtain documents that showed that R’ Meilich had a history of working in order for him to be pardoned. After a short while, papers stating that R’ Meilich worked at a factory that made milk bottles were obtained. The documents reached the right people and the president pardoned him. R’ Meilich went back to yeshiva in Kiev. Shortly thereafter, he went to learn in Kursk.

FATHER, MOTHER AND SPIRITUAL MENTOR

In those difficult times, many melamdim, maggidei shiur and mashpiim were caught and sent to jail or exile. Their wives remained living widows and the children living orphans with no material and spiritual support. The situation was dire. As a result, it was decided that older bachurim who were not yet married would take these positions.

R’ Meilich became a maggid shiur and he gave shiurim to boys just a few years younger than him. Fortunately for him, his beard was still short so that the secret police who sometimes went to where they were learning did not think he was the melamed. The talmidim themselves had beards and they claimed they were learning on their own, which was legal.

Despite this, he was arrested and jailed a few times for being a maggid shiur. He did not talk much about this era but his children heard just a bit from him. R’ Nachum said:

“For a long time, my father was responsible for a group of bachurim. He was the maggid shiur, the mashgiach, the mashpia, as well as the menahel gashmi of the yeshiva. He not only taught but took care of providing food, places to sleep, and was the father and mother of the boys aside from also being their spiritual mentor.

“The government arrested my father a number of times and he was sent for brief stays in prison. On a rare occasion he confided how he survived Pesach in jail. Every day the inmates received a small ration of bread, but during Pesach, in order to torment them, they gave the Jewish prisoners plenty of white bread. For my father it was extremely difficult and he did not know whether he would make it through Pesach alive. Nevertheless, he resolved not to allow chametz to enter his mouth, come what may. He sufficed with sugar cubes and a few potatoes.

“On the last day of Pesach he fell deathly ill. ‘If Pesach would have been one more day, I would not have survived,’ he said.

“On another occasion he said that he managed to hide his t’fillin in jail and every morning he would get up early and put them on in bed in a way that nobody would see. Despite his great care, one of the prisoners noticed the leather straps and decided to steal them.

“One morning, my father got up and to his great shock, the t’fillin shel yad had disappeared. He looked all over and then realized they had been stolen. He was disconsolate and was determined to find them. After the daily bread was distributed (it was the only food they were given that day), he gave his portion of bread to a prisoner who was a boss in the cell and told him that in exchange for the bread he had to find the stolen goods. Within a short time his t’fillin were located and returned. He fasted that day, endangering his health, for the t’fillin.”

THE BOTTLE

THAT SAVED HIM

In 5697/1937, R’ Meilich married Yehudis Segalov, from a family of rabbanim. They lived in greater Charkov.

With the outbreak of World War II, he was forcibly drafted despite the exemption he had, because during those emergency times all exemptions were void. He left his wife and baby Nachum at home. R’ Nachum told about an episode that occurred while his father was in the army:

“My father had to guard a military base. Since he was the only guard, his duty was that much greater. When Sukkos came, he decided that he had to eat in a sukka on the first night, no matter what. He somehow found out that the nearest sukka was in the home of someone who lived an hour’s walk away. He walked quickly so he could return as fast as he could. He knew that once every few weeks there was a special inspection to ensure that the guarding was being done properly. The chances were slim but he still hoped that the inspection would not take place that night.

“When he arrived at the sukka, the owner wanted to serve him meat and fish but since he was in a rush, he quickly ate a k’zayis of bread and left. When he arrived back at the base, he saw at the gate his commander who screamed, ‘You left this base without a guard in wartime. We just had an inspection and they saw that there is no guard!’

“My father knew that if they judged him now, the sentence would be severe because it was desertion during wartime. He suddenly recalled that he had with him a bottle of vodka, a precious commodity in those days. He gave the bottle to his commander who immediately relaxed. He smiled and waved a finger in warning and said, ‘Make sure you don’t run away again.’

“After a short while he was able to return home. He packed his belongings and immediately left for Kazakhstan with his wife and baby where his father was already in exile.”

IN EXILE IN KAZAKHSTAN

How did his father get to Kazakhstan?

As already mentioned, his father was the rav of the Jewish community in Kiev and he led them fearlessly. One day he was arrested for the crime of spreading Torah. This was Adar 1939. They also arrested rabbanim, Chassidim and others in Kiev, Yekaterinoslav (where the Rebbe’s father was arrested), Chernigov and other cities.

After a long incarceration in which they were interrogated and tortured, the rabbanim were exiled, each to a different location. R’ Levi Yitzchok was sent to C’ili while R’ Kaplan was sent to a village called Yani-Kurgan (about 25 kilometers from C’ili) together with R’ Moshe Kolikov and R’ Bentzion Geisinsky. According to law, the prisoners were not allowed to leave the place where they were exiled, but R’ Kaplan and R’ Kolikov left many times for C’ili in order to meet with R’ Levi Yitzchok and to assist him.

R’ Moshe Binyamin, R’ Kaplan’s son, related:

“Since my father was a ben Torah and a great scholar, they had what to talk about and they enjoyed each other’s company. When my father and R’ Kolikov went to see him, they would bring food and arranged their visit so that they could stay with him for five or six hours every time.”

After a while, the families of the prisoners were able to go to Kazakhstan. R’ Kaplan’s wife joined her husband and R’ Meilich with his family arrived afterward and joined his parents. He also visited R’ Levi Yitzchok and helped him in his final years.

At some point R’ Kaplan was forced to relocate to Kzyl-Orda where he underwent much suffering. On Yom Kippur 5704/1943, he davened in a private home which was turned into a secret shul. When they finished reciting Kol Nidrei and Maariv, everyone went home. R’ Kaplan and his son, R’ Meilich and R’ Kolikov remained to say T’hillim. The local worshipers warned them about the danger of walking in the street late at night because there were murderers roaming the streets.

Late at night, R’ Kaplan and R’ Kolikov returned home while R’ Meilich remained to rest on a bench. On their way home, ruffians beat them severely. R’ Kolikov, who was older than R’ Kaplan, fainted. They thought he had died and they left him alone while they continued beating R’ Kaplan.

With his remaining strength, he dragged himself home and managed to say that R’ Moshe was lying on the street, “Hurry and save him.” Those were his last words. He lost consciousness and throughout the holy day he was in critical condition. At the time of N’ila, he passed away, may Hashem avenge his blood.

After the passing of his father, R’ Meilich moved to Samarkand with his family. Many Chabad Chassidim went there during the war as they escaped from areas conquered by the Nazis.

The economy of the Soviet Union during the war was terrible and starvation felled many people. R’ Meilich and his family suffered from hunger, but he did not have anything to feed his wife and children. The situation grew worse until there wasn’t even a piece of bread in the house.

One day, he met the Chassid R’ Berke Chein who knew R’ Meilich’s situation and offered him a loan. R’ Meilich refused it. R’ Berke did not give up but suggested that he consider taking it. After R’ Meilich refused him time and again, R’ Berke burst into tears and said, “Meilich, I know that the situation in your house is terrible and you have no money with which to buy food. If you don’t take the loan, I feel like I just won’t be able to survive!”

With the end of the war, R’ Meilich left the Soviet Union via Lvov and from there arrived in Poking, Germany. He lived there with his family in a large refugee camp with other Chassidim. A Chabad school was started right away and he was appointed the melamed. This time, he would be able to teach Torah to Jewish children without fear.

When R’ Meilich told the Rebbe Rayatz that he was planning on making aliya, the Rebbe Rayatz gave him an important assignment:

In response to your letter about preparing to travel with a large group of religious Jews… via the coast of Marseilles, surely you will try to urge the passengers and their households to try and settle in the company of G-d fearing people and as soon as they arrive, to arrange learning in Torah classes and for their children to arrange schools and yeshivos that are G-d fearing. I would take great pleasure in hearing about the welfare of all and about their settling in. (letter from 20 Cheshvan 5709)

PASSING UP

A RABBINIC POST

R’ Meilich Kaplan arrived in Eretz Yisroel at the beginning of 5709 with his wife Yehudis and his children, Nachum, Boruch, Tova (later Yudelewitz), and Chana Sarah. Their youngest son, Aryeh Leib, was born in Eretz Yisroel.

At first they lived in a transit camp in Beer Yaakov. From there they went to Lud where some Lubavitcher families had settled. R’ Nachum tells of the difficulties of acclimating in Lud:

“My father was told that the place where we would settle was part of the city Ramle and neighborhoods would be founded there that would serve as the Chabad center of the country. He eventually found out that the people in charge in Ramle did not know that this area was actually part of Lud.

“My father did not have a job. He got an offer from R’ Shaul Yisraeli (later rosh yeshiva of Merkaz HaRav and a member of the Beis Din HaGadol) who was a relative of his. He offered to appoint my father rav of the city. ‘Take the portfolio of HaPoel HaMizrachi and we will appoint you rav.’ He knew about my father’s scholarliness and wanted a suitable rav for the city as well as to help him with parnasa.

“My father, who was new in the country, did not know the significance of the portfolio of HaPoel HaMizrachi and so he consulted with his friend, R’ Avrohom (Drizin) Maiyor. R’ Drizin explained that this would mean he was aligning himself with the HaPoel HaMizrachi political party and he should say no. My father listened and declined the offer.”

A short while later, right after the founding of Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim in Lud in Shevat 5709, R’ Meilich was appointed as the first maggid shiur in the yeshiva.

On 19 Adar, about two months after the yeshiva was founded, the Rebbe Rayatz wrote to R’ Meilich:

… I was pleased that, thank G-d, you obtained an apartment at Lud station and are regularly involved in public shiurim for adults, as well as arranging learning for the children of Anash.

R’ Meilich worked at the yeshiva for thirty years. Some of the years he worked as a maggid shiur and some of the years he was a mashgiach of the older talmidim. The talmidim found his appearance intimidating. It was enough for them to see him approaching the yeshiva building for them to run to the zal and start learning. At the same time, he treated the talmidim like a mother who is concerned for her child. When a talmid found the Gemara hard to understand, R’ Meilich would explain it to him again and again patiently. He would be especially mekarev those from North African countries whose parents were not Chabad Chassidim. He was like a compassionate father to them and he encouraged them throughout.

Even in later years, when he was sick, he continued to go to the yeshiva and served as a meishiv.

Throughout the thirty years, he never thought of a high salary or bonuses for seniority, on the contrary. He went abroad a few times to raise money for the yeshiva and after he passed away, R’ Efraim Wolf, the menahel, said R’ Meilich would donate most of his salary to the yeshiva.

RAV IN SHIKUN

CHABAD LUD

Along with his work in the yeshiva, R’ Meilich served as rav in Shikun Chabad in Lud. Shortly after arriving in Lud, he was appointed rav of the tiny Chabad community which solidified and grew. He did not receive a salary for this. All his work in rabbanus was done voluntarily and with endless devotion. He would give shiurim and farbreng in the shuls of the neighborhood and also went to other shuls in Lud to give shiurim and speak to the congregants.

He would say: When a Jew serves Hashem by learning Torah and doing mitzvos and is completely devoted to serving Him, spreading Torah to talmidim, and this is his goal and his desire and his chayus, then Hashem sends him his parnasa and the parnasa of his household like bread from the heavens. For example, in our generation there is a Jew that Hashem sends him parnasa as if it was literally bread that fell from heaven because his thoughts, speech and actions are completely in the service of Hashem.

He initiated the founding of the elementary school in the neighborhood and was involved in building the mikva. When the mikva was being built he raised money for it and wrote to the Rebbe about this. The Rebbe wrote him a letter which he ended with: May Hashem grant you success in this holy work and your work in the yeshiva which will consequently bring bracha and success in your personal matters as well. With blessings for success to all the participants in this holy work.

Whenever it was necessary to fill the rainwater pit again, he would do this taking great care with all the halachos.

Over the years he had a daily routine. He would daven Shacharis in the first minyan at the Chabad shul. Aside from his work at the yeshiva and the shiurim he gave in the neighborhood shuls, he also had chavrusas with whom he learned during the day and set shiurim that he learned on his own.

“All the shiurim and the eating and sleeping were done in an orderly way. I never saw my father idle. Even during a time when he found it hard to read due to a medical problem with his eyes, he listened to tapes with shiurim in Nigleh and Chassidus,” said his son R’ Nachum.

DEATH WITH A KISS

A few years before his passing, he had a stroke and he suffered greatly after that. Nevertheless, he continued going to yeshiva and responded to questions from people in the community.

On Shabbos Parshas Chayei Sarah 5741/1980, while his son Nachum was visiting him, he told him a d’var Torah: At the beginning of the parsha, Rashi says on the words, “the years of the life of Sarah,” that they were all equally good. How can he say this? Were all her years equally good – weren’t there ups and downs? The answer is that even when there are unpleasant things, they need to be accepted in the right way.

Two days later, on 24 Cheshvan, he went to the Georgian shul to daven Mincha. He always davened Mincha in this shul and occasionally he addressed the people with words of chizuk. R’ Meilich was standing next to the Aron Kodesh for Shmoneh Esrei when his siddur fell from his hands and his head fell back with him leaning against the Aron Kodesh.

That is how he passed away in a death befitting a Chassid who was completely devoted to others and to spreading Torah behind the Iron Curtain and in Eretz Yisroel.