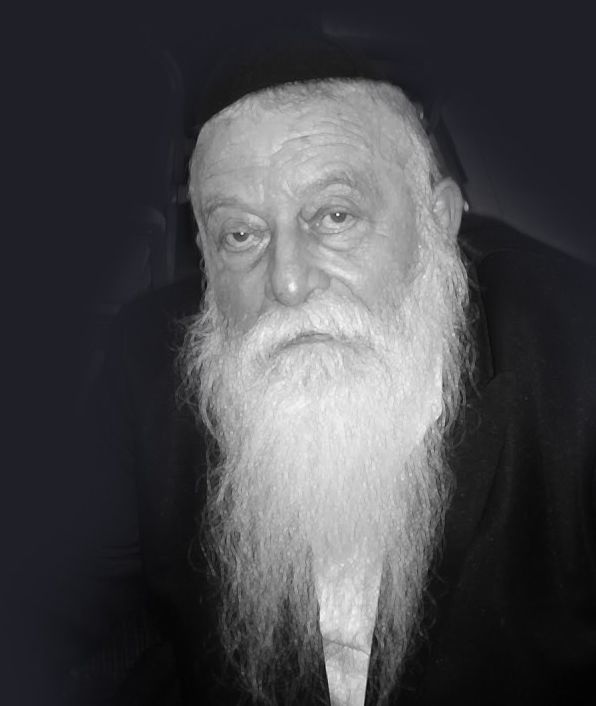

The Chassidic persona of the mashgiach and mashpia, the Chassid R’ Moshe Naparstek a”h, is engraved in the hearts and souls of thousands of students, who spent time under his influence during his over forty years in the Chabad yeshiva in Kfar Chabad. They viewed him as a p’nimius’dike Chassid, a wonderful mashpia, and a wise Chassid whose big heart was always open to them. * Along with the “hats” of mashgiach and mashpia, he also wore the hat of a farmer and every day he spent hours in the esrog orchards in Kfar Chabad, as the Rebbe told him to do. * Portrait of a Chassid.

The Chabad community sustained a great loss with the passing of R’ Moshe Naparstek a”h, mashpia in Tomchei T’mimim in Kfar Chabad for decades. He was 81.

THE EARLY YEARS

R’ Moshe, or as he was affectionately known, R’ Maishke, was born on 14 Teves 5695. His father was R’ Reuven Dovber who learned in Tomchei T’mimim in Warsaw, and his mother was Chaya Gittel. Moshe was the youngest of three brothers.

World War II broke out when he was four years old. His family was living in Shedlitz, Poland at the time.

“My first memory is of a siren and my mother came running to take me home from school. That was the last time I remember my mother holding me,” R’ Naparstek said over seventy years later.

Due to the war situation, the family escaped from Poland to Siberia where they spent the war years. Moshe was only seven years old when his mother died of starvation.

“We had to keep moving throughout the war years. We arrived in Siberia and then moved to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Although we kept moving and there was the problem of parnasa and life itself, my father put in great effort to instill in us children as much Yiddishkait as he could. My father was moser nefesh for this so that our precious childhood years would not, G-d forbid, go to waste.”

At the end of the war, his father, who had Polish citizenship, was allowed to legally cross the Russian border together with his family. He returned to Poland where he saw the scorched earth that the cursed Germans had left behind. He decided not to remain in Poland and he headed for the refugee camp in Poking, Germany where there was a group of Chabad Chassidim who had also fled from Russia. There, in the refugee camp, “For the first time in my life I encountered Chabad Chassidim, and there is where I celebrated my bar mitzva.”

R’ Moshe, then a youth, got to know the ways of Chabad Chassidim and this made a strong impression on him. He was close with R’ Avrohom Eliyahu Plotkin, R’ MM Dubrawsky, and others. He was particularly drawn to the Chassid, R’ Yisroel Neveler (Levin).

“He was a Chassidic character in the fullest sense of the word. A smart man, wise and sharp, a Chassid through and through. With all his Chassidic greatness he devoted himself to us children with incredible devotion.”

Moshe would sit for hours and watch R’ Yisroel daven and observe his Chassidic ways. “He is the Chassid who shaped my Chassidic identity,” he said years later. “Although by nature I wasn’t a particularly sedate child, I clung to him with all my might and literally followed him around. On Shabbos, for example, I would run to hear Kiddush, eat something and then quickly return to shul so as not to miss his Shabbos davening, which lasted until four, five in the afternoon.”

The Naparstek family did not stay in the DP camp for long. They continued from there to Eretz Yisroel. They arrived in Sivan 1948 and with the founding of Kfar Chabad in 1949, they joined that generation of pioneers who founded the town amid great hardships.

R’ Naparstek went to learn in Yeshivas Achei T’mimim in Tel Aviv by the mashpia, R’ Shaul Brook. Then he learned in Tomchei T’mimim in Lud and Kfar Chabad where he was a student and mushpa of the celebrated mashpia, R’ Shlomo Chaim Kesselman, from whom he heard and internalized a lot. “He is the person to whom I can attribute my entire personal development; it belongs to him.” It is said that R’ Shlomo Chaim would send young talmidim to watch R’ Moshe daven on Shabbos so they would see what t’filla is supposed to be.

The first time he went to the Rebbe was in 5719, after going through many bureaucratic hurdles which dragged on for two years. It was only a handwritten, explicit note from Ben Gurion himself that enabled him to leave the country. He spent nearly a year and a half by the Rebbe.

“Even before the hanhala of the yeshiva accepted me, the Rebbe officially accepted me. In yechidus he blessed me with ‘bracha v’hatzlacha’ in my learning in yeshiva.”

That year and a half by the Rebbe was full and packed, with R’ Moshe using every moment in the presence of the Rebbe to absorb much Torah, Chassidus and hiskashrus to the Rebbe, experiences which stayed with him for the rest of his life.

THE MASHGIACH’S ADVICE

Shortly after he returned to Eretz Yisroel, he married his wife Leah, daughter of R’ Avrohom Shmuel Garelik, and granddaughter of the rav of Kfar Chabad, R’ Shneur Zalman Garelik zt”l. He began working as a teacher in the vocational school. Some time later, he was appointed as the educational menahel of the vocational school which then had 400 students.

After a while, Tomchei T’mimim moved from Lud to Kfar Chabad and his beloved mashpia, R’ Kesselman, suggested that he work there. “I wrote to the Rebbe and the Rebbe said to accept the offer. I began my job as mashgiach in Chassidus,” a job he maintained for decades.

The mashpia, R’ Moshe Naparstek, was beloved and admired by his talmidim over the years even though part of his job was to take and enforce attendance, a job that usually creates friction between a mashgiach and the students. He earned their love since he himself felt great love for them and he served as their advocates during administrative meetings.

He once told the following story:

“Now and then, there were situations with the students that did not go smoothly. Among the hanhala there were arguments about the talmidim, as is typical in many schools. Among the staff there were those who called me the Rav from Berditchev since I tried to go easy on the talmidim.

“There was once a group of students—today they are all fine Lubavitchers—who at the time were having difficulties as far as kabbalas ol and discipline were concerned. Among the staff some maintained that we needed to be tough with them, but I insisted that we act like Hillel. I took on the entire staff but since the educational situation was really not simple, I was not confident that I was taking the right position. I decided to ask the Rebbe.

“In those days I would go to the Rebbe twice a year, for Simchas Torah and for Shavuos. All the times I had yechidus, on principle I did not ask the Rebbe about yeshiva matters. The reason for this was that the Rebbe received detailed reports from the menahel of the yeshiva, R’ Efraim Wolf, who also participated in the meetings of the hanhala ruchnis that took place twice a month, and so I knew that the Rebbe was aware of the situation.

“Since the matter was on my mind, I decided to ask the Rebbe this time, and act accordingly. Before going in for yechidus, I wrote to the Rebbe about this but in the end I did not submit this question. I figured I would bring the matter up orally. In the end, I did not bring it up during the yechidus either but something special happened.

“It was a very long yechidus and the conversation shifted to the esrog orchard that I own. At a certain point, the Rebbe motioned and I understood that the yechidus was over. I started going out while facing the Rebbe and suddenly, the Rebbe looked up (he usually sat somewhat bowed over) and I saw that he wanted to say something. Then the Rebbe said, ‘Regarding chinuch, in general, since time immemorial the approach of drawing close and ways of kindness were always the way to success, especially today, nowadays, when only chesed and ways of drawing close are the path to success. Blessing and success.’ It was a direct response to the subject on my mind and the Rebbe raised it without my asking.

“Until today, I meet students who learned in yeshiva and even if they were not able to make it in the standard track, they tell me honestly that they appreciate and are thankful for what they got in yeshiva. It is clear to me that when the approach is one of drawing close and chesed, the message sticks.”

His guidance of the talmidim was extremely down to earth. One of his students, R’ Yigal Ovadya, tells of a “simple” but wise piece of advice that he got as a student:

“I went on K’vutza in 5744. Before I went, I asked him to give me a tip about how to conduct myself at the Rebbe. He just said to me, ‘Eat well, sleep well, remember that day is day and night is night.’ I said to him, ‘I am going on K’vutza to be with the Rebbe. That’s all the preparation you are advising me to do? How about giving me a program of Chassidus to learn, or some other Chassidic practice?’ but he said, ‘Yigal, if only you kept to what I told you!’

“My first day at 770, I sat and learned. Next to me were two bachurim and I heard one of them ask the other, ‘When did you go to sleep last night?’ The other one said, ‘At four in the morning.’ ‘Why so early?’ asked the first one. ‘Because I was tired and couldn’t stay up any more.’ That is when I understood that my mashpia knew just what he was talking about. I resolved to stick to the yeshiva schedule, even though it’s not always easy to do so when on K’vutza.

“One day, the rosh yeshiva, R’ Mordechai Mentlick, said to me, ‘I see that you are particular about the s’darim and that you are learning seriously.’ He wanted to reward me for this. I told him that my reward was the precious time I had seeing the Rebbe but he did not accept this and wanted to reward me with some material item.

“This was all because of the simple advice given to me by the mashpia. I saw blessings by doing as he said.”

***

R’ Naparstek’s main job in yeshiva was as mashgiach, but he also carried out the role of a mashpia. He gave a Tanya class at the end of the Chassidus session in the evening. He occasionally farbrenged with the bachurim along with the old-time, famous mashpiim.

“Over the years I was particular about not giving a shiur in Chassidus because my job was hashgacha, and I did not want to distract myself from supervising the bachurim,” said R’ Naparstek with a smile.

“Throughout the years I was in the dormitory more than in the zal. I knew that if I wanted the zal to be as it should, then I needed to be in the dorm to make sure that everyone would sit and learn. When I felt that it was too hard for me to run around between dozens of dorm rooms and check after the bachurim, I left hashgacha and began giving shiurim in Chassidus.”

Although his job was not the easiest or the kind that is appreciated, R’ Moshe candidly said, “Out of the thousands of talmidim over the decades, I don’t think I have a single enemy because of the job I had.”

CHASSID, CHACHAM, PIKEI’ACH

R’ Moshe Naparstek was gifted with wisdom. “He was a smart man,” said all the people I spoke to when writing this article. There is a Chassidic aphorism about Chassidim needing to be smart and he was a role model of a smart Chassid.

Not surprisingly, R’ Moshe was the mashpia not only of yeshiva bachurim but also of dozens of married men in Kfar Chabad, some of them graduates of the yeshiva and some of them who “discovered” him. They found in him someone who combined cleverness and great wisdom along with deep Chassidic feeling which was focused on “to carry out the Rebbe’s wishes.” This combination became a beacon for many people who wanted direction, advice, and a path to travel at various crossroads in their lives, whether in Chassidic life, family life or other issues that came up.

“He always had time,” said one of his mushpaim. “Whenever anybody went to consult with him, despite all the things he was involved with, he always made himself available and sat down to talk, giving his full attention and with patience.”

He would regularly say – Chassidus teaches two principles: deliberation and patience. A Chassid needs to make decisions deliberately and he needs to know that nothing moves forward at high speed; to do things with patience and not in a rush.

Once again, we turn to his talmid and mushpa, R’ Yigal Ovadya of Kfar Chabad. When I asked him to characterize R’ Moshe, he raised his hands in a gesture of helplessness. “A giant of a mashpia,” he said and was unable to come up with anything else.

He first got to know R’ Moshe starting in 5741. R’ Yigal was a soldier at the time who had just started getting acquainted with Chabad Chassidus. He served in the air force and was dealing with a series of conflicts between doing mitzvos and carrying out his orders.

“I had to find solutions and I looked for someone who would understand things well with whom I could consult,” he says.

One of the main problems was davening in the morning. The day began at 7:30, but the religious soldiers who davened Shacharis were often late because of the davening. That caused unpleasantness with the officers, until finally, the commander of the base decided that the davening had to begin earlier and he gave the soldiers an additional fifteen minutes, so they had to be ready by 7:45.

“Despite the small addition, I was always late,” said Yigal. “This really irked my direct commander. I tried to speak to him, I tried to compensate him by offering fifteen minutes at the end of the day, but he did not accept that. We fought every morning.

“One day, I arrived at the yeshiva in Kfar Chabad without knowing anyone. I went over to the first talmid I saw in the zal and told him I wanted to consult with some rabbi. He pointed at R’ Moshe who stood near the entrance and wrote down who was late.

“From a distance he did not look like the kind of person I was looking for. I thought he wouldn’t understand, but since I had nothing to lose, I went over to him. He first asked me questions about myself, then he asked about my life in the army, about the orders and the schedule. Then he thought and said, ‘Then obey orders and show up at 7:45.’ I told him that in that case, I would hardly have time to daven, but he said I should still make it my business to show up on time. He also advised me to ask for a written record of my discussions with the commander about my unpunctuality.

“I didn’t have a choice; I did what he said. When I got to the base I went over to the commander and requested a written record of our interactions. He agreed and we walked to the conference room together where I spoke to him again and said I request special permission to show up each morning at eight. He looked at me and said, ‘You want to come at eight? Fine, then come at 8:15…’ I was taken aback and said I did not understand. After all, he had always insisted that I come at 7:45 and not a minute later. What happened all of a sudden?

“That same day I went back to the yeshiva and asked R’ Moshe how he accomplished this miracle. He said, ‘As long as you did not give him the feeling that he is the commander and you are the soldier, nothing helped you. But the minute you gave him the feeling that he is the commander and you will obey him, his attitude changed.’ Thanks to his wise advice, things worked out in the best possible way.”

This was how Yigal met the mashpia, R’ Maishke. “For decades, whenever I consulted with him, he always gave me the best possible advice. I have many examples to illustrate that whatever he said was right.

“Some years later, the commander of the base was replaced with a tough guy whom everyone feared. At the same time, he was an excellent commander and the military establishment loved and admired him for his ability to get things moving. I was also afraid of him, especially when I already had an administrative position and was supposed to serve as his assistant. I went to R’ Naparstek and told him I was anxious. He said to me, ‘You will do what he tells you.’ That is what I did and throughout the period when we worked together, no problems arose.

“A few years later, when I was released from the army, I got to talking openly with the commander and he told me that one time they wanted to get rid of me and the commanders above him had him come and discuss it. He got up and said, ‘If you start with him, I promise you that I am going with him.’ He had supported me, which was most unusual. I couldn’t restrain myself and said to him, ‘You are known as a tough commander. Thanks to what did I survive under your command?’ He said, ‘Because you did whatever I told you.’ Word for word what R’ Moshe advised me.

R’ MOSHE’S ESROGIM

For many years, R’ Moshe grew esrogim in Kfar Chabad. He went himself to the orchards and supervised the process from the beginning until the stage of selling them before Sukkos.

He was a farmer as well as a mashgiach and mashpia. “Kfar Chabad was founded as an agricultural village,” says Mrs. Tzippora Maidanchek of Kfar Chabad whose family kept close ties with the mashpia. “That is how it was presented to the outside world throughout the years. However, as time went on, the Kfar changed and R’ Moshe was one of the few who continued farming. This was part of his devotion and loyalty to the Rebbe.”

His involvement with esrogim began around 5720. Five years prior to that, the Rebbe spoke to R’ Mordechai Perlov of Italy about the possibility that the esrogim from Calabria would be grafted and to be properly prepared for such an eventuality. The Rebbe wanted them to take seedlings from orchards in Calabria and plant them in orchards that were free of any grafting in Kfar Chabad.

After the passing of his father-in-law, R’ Moshe inherited the orchard along with his brother-in-law, R’ Elozor Garelik. The strain of esrogim from this orchard were planted from saplings of Calabrian esrogim that were imported for this purpose so that all the esrogim in this orchard were “descendants” of Calabrian esrogim.

“Throughout the years, the Rebbe urged us to expand the orchard,” said R’ Naparstek. “Every time I had yechidus the Rebbe asked me about the orchard, down to the smallest details. The Rebbe knew the entire growth process with all the difficulties and accompanied us every step of the way. Every time we uprooted a section or transferred a section, the Rebbe got a report. When agricultural problems or diseases we were unfamiliar with arose, the Rebbe always took the position that we need to bring experts in order to solve the issues.

“For 5739 (or 5740) we looked into an offer to buy a large parcel from the Israel Land Authority, across from the print shop in Kfar Chabad, nearly forty dunam (about nine acres). At the time, temple oranges (also known as royal mandarins) grew there. The truth is, we were afraid to get involved with something so big. Forty dunam seemed too big for us (until then we had about ten dunam, a little over two acres). The Rebbe, of course, told us to take all the land offered to us. Afterward, I asked the Rebbe whether to plant in all of it, i.e., whether to uproot all the temple orange trees and replace them with esrogim or to leave some of them and plant esrogim in another section.

“The Rebbe circled the words “plant all of it,” and made an arrow, i.e., to plant it all. Of course that is what we did. The Rebbe always took the position (and this is what he wrote in his letters) that the day would come when it would be almost impossible to get Calabrian esrogim that were not grafted, and the Rebbe wanted there to be another option, reliably non-grafted esrogim in their place.”

The Naparstek and Garelik esrogim orchards took a new turn in 5751 after R’ Moshe submitted a note to the Rebbe. “That Tishrei I was at the Rebbe and was very caught up in the atmosphere of ‘I will show them wonders.’ After Sukkos, I very much wanted the esrog that the Rebbe said a bracha on so I could plant it in my orchard.

“I submitted a note on behalf of myself and my brother-in-law in which I made this request and said it was ‘to merit Anash.’

“Ten days later I got a phone call from the secretary, R’ Groner, who told me that the Rebbe instructed him to give the two esrogim that he had said a bracha over on Yom Tov to us, to Kfar Chabad, so as ‘to merit Anash.’

“Then began a long process. I was able to get fifty-four good seeds out of the two esrogim (three times chai), we cultivated the seeds into seedlings, and from those seedling we planted new saplings.

“At first we thought of designating just one section for these special esrogim, for we thought that only Anash would appreciate them. The rest of the land would be used for ordinary esrogim. We advertised among Anash about the esrogim from the strain that the Rebbe used in 5751 and people bought them, but not in the way we expected. The ‘I will show them wonders’ esrogim became popular and everyone wanted them, even other Chassidic groups, Litvish, Yerushalmim, and even Satmar Chassidim. It took a few years until we converted other sections of the orchard and planted trees that are descended from the Rebbe’s esrogim. In the end, all our esrogim are offspring of those two esrogim.”

The Rebbe kept close tabs not only on the cultivation and challenges of the orchards but also on the marketing and sales.

“I once got an enticing offer from the Esrogei Yisroel Center, that created an umbrella organization for all esrog growers in Eretz Yisroel, to join them. It was an exceedingly attractive offer and when I went to the Rebbe for Shavuos I asked him about it. The Rebbe said, ‘Regarding the marketing, you should do it on your own.’ I said, ‘But we are in Eretz Yisroel and hardly ever leave.’ The Rebbe said, ‘Nevertheless, come here, you come one time and then your brother-in-law, in order to market them.’ The Rebbe did not want us to market them through dealers and brokers.

“The Rebbe said the marketing should be done in a way of ‘l’sheim u’l’tiferes (for renown and for splendor) in a way that is suitable for us, Chabad.’ I understood from this that we have a mission to do in the marketing. Boruch Hashem, we ourselves market the esrogim and we have acquired a good reputation both for the prices and quality. We are the only place where those learning in kollel can obtain the most expensive esrog at a reasonable price. We don’t keep the nicest esrogim for those who pay more.”

R’ Moshe and his brother-in-law sent the Rebbe two beautiful esrogim every year. The Rebbe did not say a bracha over these esrogim, but he always took them out to the sukka and maybe even shook them.

“My father considered everything to do with the esrogim a big z’chus,” said his daughter, Mrs. Levin. “He considered it a shlichus to be mekadesh sheim Lubavitch.”

Throughout the years, he was always in the esrog orchards early in the morning, cultivating the produce with great care, and then he went on to the yeshiva.

“To R’ Naparstek, Torah was life. He knew how to translate the Torah into terms of daily life. There was no separation for him between the hours that he spent in yeshiva and the hours he was in the orchard. The same was true for his relationship with the Rebbe, it was all the same and with the same weightiness,” said one of his mushpaim.

SPREADING TORAH AND CHASSIDUS

In addition to his jobs at the yeshiva, R’ Naparstek would give shiurim twice a week in Chassidus in the central shul in Kfar Chabad. His shiurim, which took place every Monday and Wednesday, were on the intricate Hemshechim of 5666 and 5672. For a while he also taught maamarim of the Rebbe Rayatz.

R’ Yigal Ovadya was one of those who attended the shiurim and he was amazed by R’ Moshe’s ability to teach in a way that made the material understandable to all:

“He would usually give an introduction before teaching the topic. He would invest a lot in order to explain concepts in Chassidus and he liked bringing examples, mainly from the relationship of body and soul, so that it would be more relatable to us. It was only at the end of the shiur that he would read inside the text and explain it. At the next shiur, he would start with a summary of the previous shiur and only then would he go further.

“Sometimes he explained difficult and deep sections but he would always patiently spend time explaining every concept from every angle using parables and examples.

“It would happen, after we finished a shiur in which we saw how tremendous his knowledge was, that his Ahavas Yisroel was just as great. If it was raining and I did not have a car, he would ask to take me home despite my protests.”

The shiurim were important to him. When he found out that the day and time of a sheva brachos for one of his grandchildren conflicted with one of his shiurim, he said he couldn’t attend. “I have a shiur at that time and that is more important than anything else, even a family simcha,” he said.

***

Toward the end of his life he was sick and he passed away on 10 Nissan. He is survived by his wife, Leah, and children: Yosef Yitzchok (shliach, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina); Shneur Zalman (South Africa); Mrs. Malka Levin (Kfar Chabad, Israel); Mrs. Chaya Gita Kuperman (Kfar Chabad, Israel); Mrs. Rivka Schneersohn (Kfar Chabad, Israel); Mrs. Mina Greenberg (Beitar Ilit, Israel); Mrs. Nechama Dina Lerer (Kiryat Malachi, Israel), his siblings, as well as many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.