PART I

PART I

The Shneor School in Aubervilliers, a suburb of Paris, is known among tens of thousands of French Jews as the school that conveys Jewish-Chassidic values in a professional, sensitive way. This spirit in the school is thanks to the founders, Rabbi Sholom Mendel Kalmanson a”h and his wife, ybl”c, Mrs. Basia Kalmanson.

The Kalmanson couple founded the school “out of nothing.” They invested tremendous physical, emotional and financial efforts into it.

PART II

Shortly after founding the school, it became necessary to expand it and increase registration. They had registered children from nearby neighborhoods and suburbs. As most parents did not own their own cars, the Kalmansons had to arrange transportation to and from school.

A friend of the school, Dr. Rosen, opened his heart and wallet and donated the first car which could seat nine, or as R’ Kalmanson put it in a letter, “When necessary, we can crowd in 15-20 children.”

As they couldn’t afford to pay for a driver, they had no choice but to learn how to drive a car. The plan was then to learn how to drive a bus, so that they could enroll and provide transportation for more students.

R’ Sholom Mendel and Rebbetzin Basia received the Rebbe’s bracha, “with blessing for success in all matters,” and they learned to drive.

Right after getting a license to drive a car, Mrs. Kalmanson began driving the students in the school’s one car in which more children than were legally allowed squeezed in. She was sometimes stopped by the police and fined.

The Kalmansons knew this was only a temporary solution and that they had to be licensed to drive a bus, especially with the school’s success and the 60 students expected for the new school year of 5727.

“The Rebbe’s brachos were felt with every step we made in learning to drive,” said Mrs. Kalmanson.

Usually, someone taking a test for a license to drive a bus or truck has to take dozens of driving lessons to gain expertise in handling large vehicles. Although these were not obligatory, it was impossible without them. Mrs. Kalmanson did not have money for lessons, nor any free time. After only three lessons she submitted a request to take a test. The driving teacher was astonished. He said she wasn’t ready yet.

At the preparatory lesson the day before the test, she managed to scratch a row of cars with the bus she was driving. Her main concern was not for the car owners, because insurance took care of that, but succeeding on the test. It did not look as though she stood a chance of passing it. The teacher insisted that she have many more lessons, but Mrs. Kalmanson, not having the time nor the money, insisted on taking the test.

She nervously took the test under the critical eyes of the examiner. When the test was over, the examiner could not restrain himself, and he gaily announced, “Madame, you are a champion!”

When she happily arrived home, she saw an envelope sticking out of her mailbox. She knew what it was by the type of envelope. It was a letter from the Rebbe in response to her request for a bracha for a license. The Rebbe gave her his blessing.

The fact that she had successfully earned her license to drive a bus was a great novelty, not only because she was the first Chassidishe woman to drive a bus, but because the examiner said no woman in France had earned such a license before then. Mrs. Kalmanson was the first female French citizen to accomplish this, which generated sensational reports in the local papers.

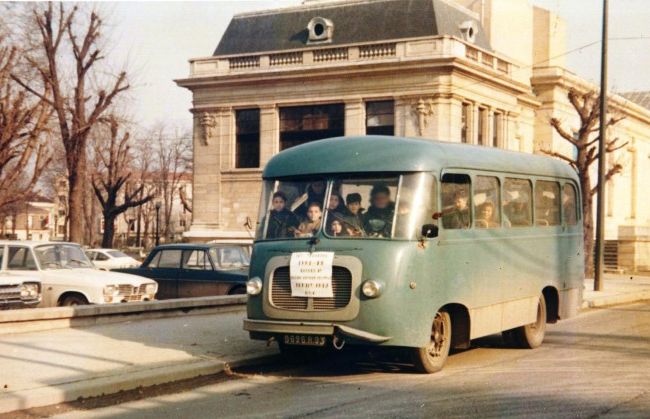

The Rebbe himself arranged for a bus to be purchased. Shortly after her husband reported to the Rebbe that she had gotten her license, the Rebbe asked R’ Sholom Mendel’s two brothers-in-law, R’ Avrohom Aharon Rubashkin and R’ Meir Simcha Chazanov, to raise the funds needed to buy a bus. The money, $3500, was soon advanced to the Shneor bank account.

PART III

Mrs. Basia Kalmanson, among her many other responsibilities, became the bus driver for the Lubavitch Shneor school. Every morning, before seven o’clock, she got behind the wheel of the bus, which later was replaced with a bigger bus, and began her rounds. She went to all the neighborhoods and picked up the children who eagerly waited for her.

Even as a bus driver, she conveyed Jewish, educational messages to the students who sat behind her. The yiras Shamayim that the children imbibed on these trips were engraved in them no less than the hours they spent within the school building. Whoever remembers those days, tells about how at each stop, even a short one, she would take a T’hillim that she kept nearby and would say another chapter. At a red light, the T’hillim was in her hands again. When the light turned green, she continued driving, sometimes after some honking from behind. The children felt as though with every stop at the light and saying a chapter of T’hillim, it was like she was asking Hashem permission to keep driving.

One time, when she stopped at a light, she took care of something important instead of saying T’hillim. When the light turned green and she began driving, one of the children called out, “But you didn’t say the mizmor for the light yet!”

Now and then, when possible, her husband drove the bus. It wasn’t always possible, because in addition to his many jobs at the school, he was also a shochet and mohel, jobs that he had to do in the morning.

Upon returning from her daily route, which began before seven and ended close to nine, she hurried home to finish dressing and feeding her little children and getting them ready for another day.

Her day did not end there, because right after sending her children to school, she went to the kitchen and began cooking nourishing food for the children in the school. In the early years, when there wasn’t a commercial kitchen in the school, and she had to bring the food from home, it was much harder. On days when her husband brought chickens from the slaughterhouse, she would remove the feathers herself, salt the chickens, clean them, and cook them. She eventually became an expert in the laws of koshering chickens and the laws of treifos. She occasionally taught the students in school the laws of salting and koshering.

There were days that she served food that required extra prep work like fried fish and fried chicken. On those days, she began her work at three in the morning. She ground the fish or chicken and prepared them until the minute she had to do her bus rounds. Upon her return, she would finish cooking them.

When the food was ready, she schlepped the pots to the school where she took a motherly concern for every student.

“Mrs. Kalmanson’s food always had a special taste, a home-cooked flavor,” said her staff. “You could tell that she put her heart into preparing and serving the food. She took care not only of the children’s ruchnius but also their gashmius and comfort.”

That’s Mrs. Kalmanson, may she live many more good years. Her days were full, as were her nights, with driving and pots, chinuch and hashpaa. She did not stop for a minute in working on behalf of the pure chinuch of Jewish children.