R’ Yaakov Noach Strasberg’s life was a series of tragedies and hardships, but he heroically withstood all the suffering and emerged a staunch Chassid and mekushar of the Rebbe.

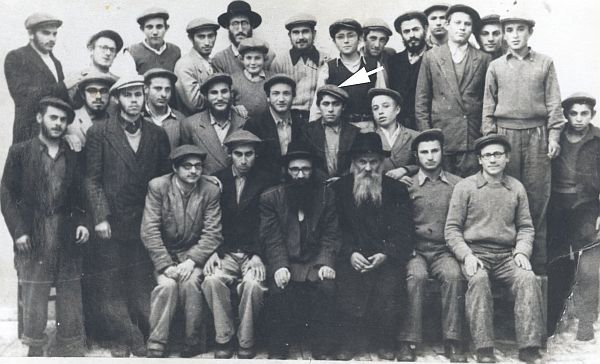

R’ Yaakov Noach (marked by an arrow) in Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim in LudSHABBOS OBSERVANCE IN SIBERIA

R’ Yaakov Noach (marked by an arrow) in Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim in LudSHABBOS OBSERVANCE IN SIBERIA

R’ Yaakov Noach was born in Tishrei 5696/1935. His parents were R’ Sholom and Alte Perel Lishner (he took the name Strasberg years later), a distinguished and Chassidishe family.

He was four years old when the family was expelled from their home in the city of Sunik. The Germans captured the city and expelled some of the Jews to Russia, including the Lishner family.

After much travail, the Lishners ended up in a Siberian labor camp where they worked hard and suffered tremendously. Even the little children, including Yaakov Noach, helped in cutting down trees. They kept Shabbos with mesirus nefesh, as related by his sister Itta Rosenberg in her memoirs (another sister was Chana Hurwitz; stories from her are also featured in this issue):

“On Fridays we worked very hard. Aside from the two trees we felled every day, we went deeper into the forest and felled another two trees and began removing the branches. The two extra trees were for Shabbos. The man in charge of supervising the work came every day and wrote down what we did. Hashem helped and he did not realize our strategy. Our father made an eiruv techumin so we could walk there. We took one of the children with us to bring us food. When we heard that the man was coming to check what we did, we took out the food and said we were resting now. That is how we spent all the Shabbasos.”

When war began between Germany and Russia, the family left that place and together with other exiles sailed to Novosibirsk. From there they traveled to Samarkand in Uzbekistan.

LEARNING TORAH WITH MESIRUS NEFESH

Upon arriving in Samarkand, they found the city full of refugees. This made it hard to find a place to live. For several months, they lived without a roof over their heads. Contagious diseases broke out among the refugees, and Yaakov Noach and his sister became sick and were hospitalized.

After they recovered and left the hospital, the parents found an attic, completely bare. This situation was described at length by Mrs. Rosenberg:

“My mother took the two children out of the hospital and did not have even a piece of bread to give them. She cried like a little girl. The winter of 5702 began and it was difficult and cold, and we had nothing with which to warm ourselves. There was no food and no way to earn money, and we starved. In order to obtain a piece of bread, you had to stand on a long line from the night before. Ruffians pushed their way through, and by the time it was my turn, they said there was nothing left.”

In Adar of that year, his brother Dovid became sick and died. In the summer, Yaakov Noach and his mother became sick and he returned to the hospital, but this time the illness was more severe. When they left the hospital, they had to be taught how to walk again.

Their suffering wasn’t over. The day after Yom Kippur 5703/1942, the father, R’ Sholom went out to try and sell a pack of cigarettes in order to bring food into the house. As he stood in the market, he was arrested by policemen who accused him of black marketeering.

He was imprisoned and beaten until he died, may Hashem avenge his blood. That was 20 Tishrei. He was buried in the cemetery in Samarkand.

Yaakov Noach was seven when he was orphaned. The suffering he endured was so great during those years that not a single memory remained with him of his father and the seven years he spent with him.

Yaakov Noach was placed in an orphanage where they tried to prevent him from keeping Torah and mitzvos. At the first opportunity he ran away, as his sister describes:

“The situation grew worse. My mother had no choice but to place her three little children in an orphanage. My sister Taube joined them. After a week, we went to visit them and it was Shabbos. Taube ran to us crying, ‘Yaakov Noach disappeared and probably ran away, but to where?’ We immediately ran in all directions and found him as he was running. Seeing us, he burst into tears. ‘They take my yarmulke and tzitzis away. I don’t want to be there.’ Of course, we took him home.”

Even as a young child, Yaakov Noach was strong-spirited and did not cave in to pressure at the orphanage. He wanted to keep mitzvos no matter what, despite knowing that if he remained there he would be well fed, and if he went home, he would starve.

When he was eight, he began learning in the covert yeshiva. However, because he did not have shoes, since they were sold for medicine that was needed for him and the family, his mother carried him there every day.

At that young age, it was apparent that Yaakov Noach was very bright. R’ Meir Gruzman, a maggid shiur in Tomchei T’mimim in Kfar Chabad, who was one of the talmidim in the underground yeshiva in Samarkand, relates:

“What stood out about our learning was that it was done under the greatest privation which is hard to describe in words. We cannot relate to it today. We starved. The fact is though, that despite the hardships, we sat and learned. We not only learned; we toiled in learning. That is a childhood memory that remains with me.

“It is impossible to forget Yaakov Noach, a boy of eight-nine at the time, who sat and learned, toiling in his studies like any talmid in yeshiva. It was obvious that he was one of the better heads in the group.”

A SHARP STUDENT

During World War II, Yaakov Noach lost many of his extended family members. After the war, Erev Shavuos 1946, the Lishners exercised their rights as Polish citizens and crossed the border into Poland. From there, they went to the displaced persons camp in Poking, Germany. There, Yaakov Noach joined the talmidim in the Tomchei T’mimim that was established.

On 10 Kislev 5709, the Lishners left the continent that was soaked with their relatives’ blood and sailed to Eretz Yisroel. The voyage took a month, and on 11 Teves they anchored in the port of Haifa. From there, they were taken to a camp for immigrants in Pardes Chana. They remained there for two weeks until Chabad Chassidim came and brought them to live near the train station in Lud where a Chabad community was forming.

R’ Yaakov Noach went to learn in the Chabad yeshiva in Tel Aviv where he assiduously studied Nigleh and Chassidus until the yeshiva was established in Lud. Then he, along with a group of bachurim, went to learn in Pardes.

The teachers and hanhala were amazed by the extent of his knowledge, even though most of his childhood years he was unable to learn. R’ Boruch Shimon Schneersohn, rosh yeshiva of Tchebin, who served at the time as rosh yeshiva in Tomchei T’mimim, said about him, “Considering his wide-ranging knowledge and sharpness, if he would have remained in yeshiva to learn after he married, R’ Yaakov Noach would have been one of the distinguished roshei yeshivos.”

His brother-in-law, R’ Avrohom Meizlich, added, “During the years that he learned in Lud, he sat and typed the entire Hemshech 5666. Thanks to him, this Hemshech was available to the Chabad Chassidic community.” R’ Meizlich described him as “a man of truth who did not tolerate falsehood at all. He only spoke the truth and conducted himself in a truthful manner.”

MANY YEARS IN 770

While learning in Pardes, he yearned to go to the Rebbe. After much effort, on Chol HaMoed Pesach 1956 he was given a visa for the US. It was sent to him by Rashag with the intervention of R’ Avrohom (Maiyor) Drizin, a member of the hanhala of the yeshiva. His joy was not long lasting though, since the hanhala of the yeshiva in Pardes told him they did not want such a young bachur going to America and said he had to continue learning in Eretz Yisroel.

R’ Yaakov Noach did not give up. He exerted tremendous effort, and after Shavuos he left for France for the purpose of reaching the Rebbe as soon as possible. In the meantime, he sat and learned in the Chabad Yeshiva in Brunoy while waiting for the papers that would allow him to continue his journey. Eight months passed and on Erev Rosh HaShana 5717 he finally arrived in New York with the help he received from R’ Nissan Nemanov, mashpia in the yeshiva in Brunoy.

R’ Yaakov Noach spent close to ten years in 770. “Those were the early years of the Rebbe’s nesius, and R’ Yaakov Noach’s conduct reflected that of a soldier who is subservient to his master with mesirus nefesh,” described someone who knew him from 770 back then.

HIS HOSPITALITY

Shortly upon returning to Eretz Yisroel he married his wife Shulamis, daughter of the mashpia, R’ Yehoshua Mordechai Lipkin.

Their home was open to guests, which their son Yoske of Crown Heights describes:

“My father loved having guests. In shul in Yerushalayim, if he saw a person that nobody else was looking at, whether this was a weekday or Shabbos, he would invite him. He once told me: In Crown Heights there are many guests. The mitzva is not only to host the bachurim. If you see someone who is not desirable for whatever reason and is not invited, you invite him.

“For my father, hospitality was ingrained in his soul.”

HIS HISKASHRUS

R’ Yaakov Noach’s hiskashrus to the Rebbe was special. He was always particular to carry out what the Rebbe said. He went to the Rebbe nearly every year. One year he returned from 770 with a window frame. When his family asked him about it, he said that he found it in the yard of 770. There was a window in the big zal that was replaced. R’ Yaakov Noach, with his great fondness for the home base of the Nasi Ha’dor, felt it was a z’chus to take the old frame back home to Yerushalayim.

His son describes his father’s hiskashrus:

“He was utterly battul to the Rebbe. One time, when he had legal problems, I asked him why he didn’t turn to the Rebbe. He said to me that he did not want to bother the Rebbe with his material concerns. In yechidus too, he never asked for brachos for material things.”

MAN OF TRUTH

Before he married, R’ Yisroel Jacobson asked him to take the job of running the yeshiva in Newark. R’ Yaakov Noach’s response was, “If I accept the job, I will have to raise funds in various places and deal with wealthy people and I will have to flatter them. I am not capable of living with that kind of falsehood.” This expressed his inner unvarnished truth, a trait that cost him a job.

About thirty-five years ago, he started the Chabad shul in Mattersdorf in Yerushalayim together with R’ Eliezer Perlstein. They were given land for the shul but some locals, most of them Misnagdim, interfered with the construction. R’ Strasberg and R’ Perlstein persisted and had a beautiful Chabad shul built.

The troubles did not end. On a few Shabbasos, people who went to daven Shacharis there found the shul locked. The opposition also interfered with the Seudas Moshiach, but R’ Strasberg remained undeterred. He fought for the existence of the shul until everyone made peace with it.

In the final months of his life, he was stricken with late stage cancer. With superhuman strength he kept his suffering to himself and tried not to depend on others and not to be a burden on his family.

About a day before his passing, he was released from the hospital. He returned home and even went out to take care of things. That evening his condition deteriorated and he was taken to the hospital.

The next morning, his son-in-law, R’ Elimelech Bienstock, put t’fillin on him and read the Shma with him. Shortly afterward, on the morning of 13 Menachem Av, he passed away at the age of 66.