In this interview, Rabbi Shloma Majeski responds to questions like: How can a real cheshbon ha’nefesh be made, examining all the sins of the previous year, while still remaining joyful?

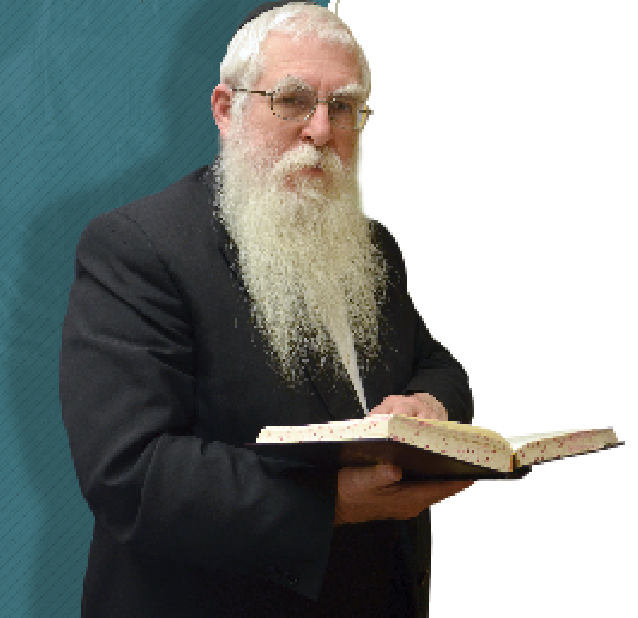

To many of us, the concept of “doing teshuva” is mainly associated with the month of Elul, the month of teshuva. But to the mashpia, R’ Shloma Majeski, dean of Machon L’Yahadus in Crown Heights, “doing teshuva” is an inseparable part of his avoda year-round as he guides baalos teshuva.

To many of us, the concept of “doing teshuva” is mainly associated with the month of Elul, the month of teshuva. But to the mashpia, R’ Shloma Majeski, dean of Machon L’Yahadus in Crown Heights, “doing teshuva” is an inseparable part of his avoda year-round as he guides baalos teshuva.

R’ Majeski combines unusual scholarship and Chassidishkeit with a profound understanding of the psychological struggles and spiritual difficulties of the modern age. In his youth, he was chosen for the first group of talmidim-shluchim to Australia who enjoyed rare kiruvim from the Rebbe. Later, he was appointed dean of Machon Chana in Crown Heights.

R’ Majeski, a lecturer on Chassidus with the audio Chabad Heritage series and the Chassidic Philosophy series, is the author of the books in English: The Chassidic Approach to Joy and A Tzaddik and His Students – the Rebbe-Chassid Relationship, as well as a series of booklets called Likutei Mekoros with sources from the Written and Oral Torah and the Rebbe’s teachings about the Rebbe’s eternal life and the identity of Moshiach.

For 18 Elul, about which the Rebbe Rayatz says that “Chai Elul is the day that brought and brings a chayus in Elul; Chai Elul gives a chayus in the avoda of ‘ani l’dodi, v’dodi li,’” we spoke with R’ Majeski about the novel approach of Chassidus to understanding the teshuva process of the month of Elul including the special novel insights of the Rebbe.

WHY IN THE MONTH OF ELUL?

Before we speak about the chiddush that Chassidus brings to understanding the month of Elul in general and teshuva in particular, why did Chazal establish a month for the avoda of teshuva? Unfortunately, we sin all year, so why focus on teshuva in this month? Do we not need to do teshuva the rest of the year?!

Those who think that teshuva only needs to be done in Elul, are mistaken. We need to do teshuva all the time! Every weekday, we say in Shmone Esrei, “and bring us back before You with complete teshuva.” Most of the days of the year we say tachanun and confess our sins. In the bedtime Shema, we do teshuva. That means, teshuva is a central component in the life of a Jew all year long.

At the same time, in Elul there is an emphasis placed on teshuva, beyond what is done the rest of the year. The simple explanation appears in Kitzur Shulchan Aruch that begins the laws of the month of Elul as follows: “The first of Elul until after Yom Kippur are yimei ratzon. Although, throughout the year, Hashem accepts teshuva from those who return to Him sincerely, still, these days are more propitious for teshuva, being days of mercy and yimei ratzon. This is because, Moshe went up Har Sinai on Rosh Chodesh Elul to receive the second Luchos and he remained there for forty days. He descended on the tenth of Tishrei, at the completion of the Jewish people’s atonement. Since then, these days are designated as yimei ratzon and the tenth of Tishrei is Yom Kippur.”

In addition, the Rebbe explains in various sichos and letters why Elul specifically is called “the month of accounting,” since the rest of the year we need to focus primarily on positive avoda and less on self-examination. The Rebbe compares this to a businessman. If he is constantly calculating income and expenses, this will cut down on his motivation to keep working and the business will run into the ground. During the year we move the business forward and just once a year do we make an “annual balance.” In a Jew’s life, during the year he needs to do more mitzvos, more Torah learning, etc. Elul is the time for an annual evaluation.

In a sicha (Re’eh 5710), the Rebbe says that the idea of making a general accounting (as opposed to a review of that day alone) every day is the counsel of the yetzer, so that a Jew be occupied with accounting rather than Torah and avoda. The Rebbe also says that a proper accounting is likely to cause damage by making a person despair. This is why we defer the accounting to Elul, a time when the 13 Attributes of Mercy are shining, and along with a cheshbon ha’nefesh a person knows that Hashem will forgive him and he won’t fall into despair.

Chassidus also brings other times that are suitable for teshuva and a spiritual accounting: 1) every night in the bedtime Shema; 2) Thursday night; 3) Erev Rosh Chodesh. The common denominator of these times is that a period of time is ending and a new one is beginning. These times occur every day, every week, every month and every year.

The Rebbe once explained what is told about Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai, that before his passing he told his students, “I do not know which path they will be leading me on,” that since he was occupied his entire life with fulfilling his mission and did not give a thought to his spiritual standing, it was only before his death, as he faced this transition, that he thought about where he was holding.

Throughout the day, we need to be busy with Torah and mitzvos and there is no time for a cheshbon ha’nefesh; it’s time for action. Only at night, when the day ends and on a “small scale” the time for work has ended, is it the time to think about the day and how tomorrow can be better. The same is true for the end of the week and the end of the month, and more generally at the end of the year. Throughout the year, a person is busy and has no time to think about his spiritual standing. The end of the year is the time to make a cheshbon ha’nefesh and correct what needs improving.

A HAPPY CHASSIDISHE TESHUVA

Chassidus illuminates every subject with an inner light and special chayus. How did the avoda of teshuva look before the revelation of Chassidus and what did Chassidus innovate?

Teshuva is to correct that which was lacking in observing Torah and mitzvos. In order to understand what Chassidus innovated with teshuva, we need to take a step back and reexamine the innovation of Chassidus in general, when it comes to Torah and mitzvos.

Before the revelation of Chassidus, the 613 mitzvos were perceived as 613 commandments, orders. When a person fulfilled them, he earned Gan Eden; someone who transgressed them, G-d forbid, earned Gehinnom. When Elul came around and a Jew saw how many sins he accumulated over the year and how few mitzvos, he was apprehensive about the thought of Gehinnom awaiting him and was disappointed over the diminished portion of Gan Eden he was going to get. If he did not do teshuva, he would pay dearly. These worrisome thoughts pushed him to do teshuva in order to erase his sins and save himself from punishment. He also tried to do additional mitzvos so his Gan Eden would expand.

Chassidus revealed that Torah and mitzvos are not merely a collection of orders; they are, primarily, 613 possible ways to connect to Hashem. In addition to the meaning of a command, a mitzva’s inner meaning is connection. When a Jew does a mitzva, he connects to Hashem and when he sins, he disconnects from Hashem. In Elul, the main avoda of teshuva is not to diminish punishment or increase reward; it is an avoda of closeness and renewed connection with Hashem.

The Alter Rebbe said that teshuva pertains to every Jew including Torah scholars. At that time, Misnagdim opposed this because, to their thinking, teshuva is only for sins and how could you say that gedolei Yisrael who learn Torah day and night, need to do teshuva?

The Alter Rebbe innovated that the concept of teshuva is mainly a process of the neshama returning to its source. He said that the verse, “and the spirit will return to the G-d who gave it” is not limited to when a person dies, when the neshama parts from the body, but even when the neshama is in the body for many days and years; then too, it needs to return to Hashem.

Before the neshama comes down to this world, it is unified with the G-dly light, completely nullified before it, and it apprehends G-dliness on a very high level. During the neshama’s descent to this world, it is very far from the “light of the countenance of Hashem.” The love and fear of the neshama when it was up above is incomparable to the love and fear of Hashem when it descends to this world. Therefore, even when there is a G-d fearing Jew who is particular about all aspects of Torah, his neshama is very distant from Hashem. All his life, he needs to try and return it and get it close to its source, Hashem.

The main focus of teshuva, as Chassidus sees it, is not to be saved from punishment but to get close to Hashem. This sums up the difference between an Elul without Chassidus and an Elul with Chassidus. Someone who does not learn Chassidus, thinks about himself the entire Elul, about the punishments he can expect to get and the little bit of reward when Hashem decides his fate on Rosh Hashana. For someone who learned Chassidus and conducts himself in the ways of Chassidus, his thinking during Elul is mainly about Hashem and the need to get closer and closer to Him.

Chassidim would tell about friends in their youth who parted ways when they grew up, one going in the ways of Chassidus and one in the ways of mussar. They met again after many years and when the Chassid noticed that his friend was sad, he asked in surprise: I see that you are blessed with a large family and have married off several children and even have grandchildren. Your spiritual situation is also good and you give shiurim in your community. Why are you sad?

The Misnaged answered: Everything you said is true but it all means nothing to me since all my life I have wanted to be a Someone and I am still a Nobody.

The astonished Chassid said: What an upside-down world! If only I was in your situation! All my life I’ve wanted to be a Nobody and unfortunately, I am still a Somebody…

When the main point is “me,” Elul is devoted to my standing, i.e. did I do well this past year or did I fail? If I conclude that I transgressed many things this past year, the main problem is that “I” was not successful. The result is a month of crying both because of my personal failure and the fear of what I can expect in the coming year.

However, when the main point is getting close to Hashem, Elul is devoted primarily to an effort in getting close to Him. When the avoda of teshuva has the feeling of closeness to Hashem, the feeling is one of happiness!

The Chassid R’ Yosef (who was the uncle of the Tzemach Tzedek) was somewhere at the start of Elul and sitting with other people when one of them said, “The sad days have begun.”

R’ Yosef said: “Why? On the contrary, happy days have begun! In Elul, the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy begin to shine and it’s like the King going out to the field, the drawing close of the light-source to the spark. So the happy days have begun.”

EVEN THE CRYING IS WITH JOY

It’s not a bit much to turn Elul into a happy month? It’s brought in sefarim that the avoda of Elul is alluded to in the verse, “and she cries … for a month.”

Crying does not contradict the avoda of simcha. With the right perspective it is possible to attain tears of joy. The Rebbe says in the sicha of Re’eh 5748 that out of love and closeness and yearning for Hashem, it is possible to attain tears of joy, like Rabbi Akiva who cried when he said Shir Ha’Shirim as a result of the cleaving of his soul to its source, beyond what the soul can contain.

The story is told of a community of Chassidim who were looking for a baal tefilla for the Yomim Noraim. After some candidates auditioned and they picked one of them, one of those who hadn’t been picked complained: I know that the chazan that they picked was chosen because of his crying during the davening; I also cried!

The gabbaim said: It’s true that you both cried but you were thinking of yourself the entire time which is why you cried when you said, “For you are dust and to dust you will return,” while the chazan who was chosen thought about connecting to Hashem which is why he cried when he said, “It is true that You are first and You are last …”

In maamarim of Chassidus on the verse, “V’yasfu anavim b’Havaya simcha,” it is explained that when a person is humble, this brings him the greatest joy. When a person is focused on himself, he has no chayus and simcha, but someone who learns Chassidus, even when he thinks about sins and mitzvos, he does not focus on his ego, whether he succeeded or failed; he focuses on Hashem, on whether he got close to Hashem or grew distant. And if he grew distant, how to get close once again.

The avoda of simcha in Elul was intensified all the more when the Alter Rebbe analogized the month to the time that the “King,” i.e. Hashem, is in the field, and whoever wants to, can approach Him, and He accepts everyone graciously and smilingly. How could you not be happy after contemplating the details of this wonderful mashal and nimshal?!

The Rebbe once responded (Shabbos Nitzavim 5734) to the complaint leveled against Chassidim, why did they have joyous farbrengens in Elul when these are days of mussar. The Rebbe said that when a Jew knows that in Elul the King is in the field and He approaches man as he is, in the field, this generates joy. This is not a contradiction to the honor of the King; on the contrary. If he were to appear downcast and depressed before the King, that is not giving honor to Him. In fact, that is the opposite of the honor of the King. There is a need for embittered feelings, and for real, over all of those things that are against the King’s wishes but that is the pain of the body, and the pain of the body should not interfere with the joy of the soul!

Before the Yom Kippur War, when the Rebbe asked for children’s rallies to be held everywhere, the Rebbe said to explain to the children this mashal of the King in the field. He said that this mashal pertains especially to little children, which means that the change in approach to Elul needs to filter down even into the preschools and elementary schools.

THE KING IN THE FIELD IN THE SEVENTH GENERATION

Despite it all, in earlier generations, the month of Elul was characterized by seriousness and gravity, as you can read in the Rebbe Rayatz’s description of the “air in Elul” in Lubavitch, how already on Shabbos Mevorchim Elul the atmosphere of seriousness could be felt.

First of all, whoever reads the Rebbe Rayatz’s description closely about the atmosphere of Elul in Lubavitch, will discern that there was no atmosphere of being down in Lubavitch, and definitely not depression. It was a serious, inspired atmosphere of connecting to Hashem, which found expression at the appropriate times in feeling the sweetness of G-dliness and even with joy. We can see this in the following excerpt in which the Rebbe Rayatz describes the atmosphere in the cheder sheini (the side room where the “ovdim” would daven) which combined pleading, bitachon and simcha:

The first is singing a Chabad melody to the words “blessed be He who decrees and fulfills,” the second is saying the words “gracious and compassionate,” and the third one is saying “and they all praise and glorify.” Another person davening is in the middle of “Ahavas Olam” and says a few words, whose meaning fills each word with great sweetness of understanding, yearning to connect, with such an imploring voice that you can feel that each word is lifting up the davener and he is rising higher and higher! He is getting ever closer to the “point,” such that he is about to reach his goal. The tune of supplication of “hasten, and bring upon us blessing and peace;” the quiet pleasant melody of “and lead us speedily upright to our land;” the confident voice with which he says “for You are G-d who performs acts of deliverance;” and the joyous voice with which he says “and You have brought us near, our King, to Your Great Name” – provide him with the strength to say “Shema Yisrael.”

At the same time, in the “seventh generation” there is definitely more of an emphasis on the avoda of simcha in Elul. This would seem to be connected with the emphasis the Rebbe placed, over the years, on the fact that the King is in the field, one of the main reasons for simcha in this month.

This mashal of the King in the field was revealed in the time of the Alter Rebbe but none of the Rebbeim dealt with it and analyzed it as much as the Rebbe did throughout the nesius. Dozens of maamarim and numerous sichos were devoted to explaining this mashal in detail.

In one of the sichos (Shoftim 5748), the Rebbe asks: Since there cannot be greater joy than that Hashem receives each one of us “graciously” and “smilingly,” why is there no commandment in Shulchan Aruch or at least in sifrei Chassidus, to be joyous in the month of Elul?

The Rebbe’s answer is that the simcha of Elul is so great and deep that it is beyond the category of a command (even the category of a command in the form of a custom cited in ethical works). The Rebbe goes on to extol the quality of joy in Elul which derives from “I am to my Beloved, and my Beloved is to me,” from the very fact that the essence of a Jew’s existence is connected to the essence of Hashem. The Rebbe concludes that the simcha of Elul which comes from the King being in the field, from the Jewish people being bound up with G-d’s essence, is beyond limitations and therefore, it is not in the category of a command and obligation.

The following Shabbos (Teitzei 5748), the Rebbe raised the bar of simcha even higher and said the sicha about the need for a special joy for the sake of bringing Moshiach.

BOTH SIMCHA AND MERIRUS

Along with the great G-dly revelation expressed in the mashal of the King in the field, we need to make a cheshbon ha’nefesh. Most people know that the conclusion of that accounting will not be “nectar and honey,” so this will most certainly lead to great merirus. How does that fit with simcha?

The Rebbe addressed this very question in the sicha of 18 Elul 5712 and even made the question based on the wording of one of the aphorisms of the Rebbe Rayatz. He then proceeded to demonstrate that not only must all matters of Elul (even the merirus) be with a chayus and simcha, but the simcha is a prerequisite to everything having to do with Elul. Without the preface of simcha, there could be nothing, including merirus.

Similar to what we explained before about the difference between a Chassid and a Misnaged, that a Misnaged thinks about himself and a Chassid thinks about Hashem, when the merirus stems from the fear of the punishment from Hashem, in children, life and health, that is a limited merirus, relative to the degree of the punishment that he fears. But when a person learns Chassidus, he understands that all his actions and avoda, whether positive or negative, “affect” the very essence and being of Hashem. That means that every mitzva that he does causes delight in Hashem’s very essence and every absence of a mitzva, or a sin that he does, causes a lack, as if that were possible. As such, since Hashem is not limited, the merirus caused by undermining k’vayachol Hashem Himself is an infinite merirus, and when a Chassid makes a real accounting, he attains this tremendous merirus!

Paradoxically, the only way to attain this enormous merirus is by having simcha first. Why? Because without simcha, knowing his spiritual state he would never be able to awaken in himself the feeling that his actions affect Hashem Himself. It is only when he works on himself to be joyous, and simcha breaks through limitations, that this lifts him to his true state where he is like a child of Hashem, all the way to his source in Atzmus, and then he will feel the extent to which his divine service matters up above.

MORE SIMCHA FOR THE GEULA!

That only makes the question even stronger if the cheshbon nefesh of a Chassid leads him to even greater merirus than the merirus following the cheshbon nefesh of a Misnaged! How can merirus and simcha go together?

First of all, the Torah does demand of us that we combine the two, for the Rambam writes that we need to do all the mitzvos with joy and that includes the mitzva of teshuva. If this is so for all the mitzvos, all the more so with the mitzva of teshuva by which a person becomes beloved to Hashem; surely this necessitates simcha.

How can both be combined? The Rebbe brings the advice of the holy Zohar that there needs to be “tears implanted in my heart on this side and joy implanted in my heart on the other side.” The feeling of distance from G-dliness, which derives from the animal soul, causes him to feel merirus, and the fact that he is doing a mitzva (Hashem’s will), which derives from the G-dly soul, makes him happy.

The Rebbe explained the need and ability to combine the joy within the merirus in 5712, but since that time we have advanced toward the Geula, so that in the maamar “Margela B’Pumei D’Rava” 5746, the Rebbe declared that “merirus in teshuva does not pertain to this latter generation of ours, the generation of the ‘footsteps of Moshiach.’ This is since, in our generation, we no longer have the strength for merirus etc. and we need great empowerment and encouragement etc. Therefore, the avoda of teshuva in our generation is precisely from simcha… and there should not be the inyan of merirus at all.”

Even more so, in 5752 (sicha Shabbos Parashas Noach), the Rebbe said that even when a person makes an exact accounting, there is the need to negate the feeling of pain and merirus, since the focus should not be on seeking out faults in one’s personal avoda but on elevating oneself to a higher level and world. To be completely immersed in Torah and tefilla so that all of the negatives are pushed aside and nullified. The Rebbe says that on a deeper level, when a person makes a proper accounting he needs to feel that the entire intention behind the descent is for the sake of the avoda of teshuva, which reveals the power of the bond that a Jew has with Hashem even in his lowly state. Therefore, the act of making an accounting and doing teshuva will be done with a feeling of joy and pleasure!

In practical terms, the avoda of teshuva contains two inner feelings, regret for the past and resolve for the future. When the emphasis is on the regret, clearly this will come along with feelings of merirus. However, when the emphasis is on the future, and this is what is required from us in these times that we are living in, then this is accompanied by great joy. Similar to what the Rebbe said in the summer of 5751 regarding the study of the topic of the building the Beis Ha’Mikdash, that the learning should not be from the overpowering feeling of mourning and the need to fix the problem, but out of a sense of yearning and desire for the quality and perfection of the Third Beis Ha’Mikdash.

The Rebbe laid out this course in a number of sichos over the summer of 5751 and winter of 5752, which is all primarily based on the Rebbe’s radical innovation that in our generation the main avoda of teshuva is the higher level of teshuva referred to as teshuva ila’a:

It is brought in Tanya that teshuva tata’a is over sins, and therefore elicits feelings of merirus; whereas teshuva ila’a is not about transgressions but the return of the soul to its source, which is accomplished with joy and pleasure. The Rebbe innovated that since the generation as a whole is ready for Geula, although a person is aware of his individual transgressions and needs to correct them, the general avoda of teshuva is teshuva ila’a, which needs to be, as mentioned, from a place of joy and pleasure.

ACCEPTING THE KINGSHIP OF MOSHIACH

The Rebbe says that every subject needs to be permeated with Geula and Moshiach. What connection is there between the teshuva of the month of Elul and Geula?

First off, it is known that the fifth acrostic of the month of Elul – ashira l’Hashem va’yomru leimor – is connected to Geula, as this verse was said at the “song of the sea” that alludes to the future song that the Jewish people will sing in the time of the Ultimate Redemption.

Beyond that, we need to remember that the month of Elul is a preparation for Rosh Hashana, whose main theme is Kabbolas Ha’Malchus, accepting upon ourselves Hashem as King. As the Tzemach Tzedek writes in Derech Mitzvosecha, the true acceptance of the kingship of Hashem is by the Jewish people accepting upon themselves the Jewish king of flesh and blood. The Rebbe adds in the sicha of Erev Rosh Hashana 5752 that the complete perfection of the kingship of Hashem is specifically through the acceptance of the kingship of Melech Ha’Moshiach. These words are the basis for the practice that has been ongoing since 5753, that before the blowing of the shofar on Rosh Hashana, we intensify the acceptance of the kingship of the Rebbe Melech Ha’Moshiach with the proclamation of “Yechi Adoneinu.”

It follows then, that the month of Elul is the most appropriate time to strengthen ourselves in the acceptance of the kingship of the Rebbe Melech Ha’Moshiach. As Chassidus explains, there is a difference between “accepting the kingship” and “accepting the yoke” (kabbolas ol), in that accepting a yoke is relatively external and it is as if we are doing the mitzva because we have been compelled. Accepting kingship, on the other hand, is much more internal and goes much deeper, in that a Jew is committing his entire being to the King and as a result, his intellect and emotions also operate in line with the will of the King.

That is how we need to approach accepting the kingship of the Rebbe as Melech Ha’Moshiach; we need to commit ourselves to the Rebbe with our entire beings, so that the result will be that we learn all of his sichos and maamarim and fulfill all of his directives, until his true and complete revelation, teikef u’miyad mamosh! ■