PART I

PART I

One night in Teves 5779, the cellphone of R’ Zushe Zilberstein, shliach of the Rebbe in Montreal, rang. He answered the phone with no warning as to what drama he was about to take part in.

On the line was someone he did not know, who introduced himself as Emil.

“I need your help,” he began. “Five days ago, an old man died here, but he hasn’t been brought to burial yet since the hospital, Jewish General Hospital, refuses to release him.”

“Why not?” asked R’ Silberstein.

“It’s complicated. The man is Jewish but has no immediate family; he lived alone. He used to be a doctor and I was a patient of his. We kept in touch even after he retired. Since he suffered from dementia toward the end of his life, he had two caretakers, one Jewish and the other not. The non-Jewish caretaker left Montreal a year and a half ago for France. Before she left, she arranged for an acquaintance of hers, a doctor of Arabic origin, to supervise the care of the deceased. It was he who informed her of the man’s death.

“A few problems arose. First, we do not know whether or not he has a will. Furthermore, the gentile caretaker insists on his being buried in a Christian cemetery, claiming he is Christian, while her colleague, the Jew, says he was a Jew and wants him to have a Jewish burial. This is why the hospital has not released him; they want both government appointed caretakers to sign the forms. Five days after his passing there is still no progress, and this is surely causing the soul to suffer. He is a meis mitzva.”

The man added another important detail. “As far as I know, the man has a cousin in Vienna. Legally, since the man has no other relatives, she can give the hospital the authorization to release him for burial. For four days now, we are trying to locate her, but she has not answered the phone. Nobody knows whether she is alive or not.”

R’ Silberstein wrote down the information provided by Emil and got to work.

PART II

That same day, Monday, 23 Teves, he called Rabbi Avi Biderman, one of the shluchim in Vienna. After friendly introductory remarks, R’ Silberstein told him the story and asked for help.

“Many attempts were made to reach the relative, but they were unsuccessful. Could you please try and reach the cousin and get her consent for the burial?”

R’ Biderman of course agreed to help and immediately tried calling the woman who was over 80. Throughout that evening and the next day, R’ Biderman kept calling the number he had been given, but nobody answered. He realized that if he delayed, it would be too late to help the deceased. He went to the address that he was given, in an attempt to meet the woman face to face.

That day was the first of January, a day off from work, and many people were on vacation outside the city. This is why R’ Biderman wasn’t too hopeful about meeting the woman at home; but he felt he had to try.

When he arrived at the address, he saw it was a large building with many apartments. The main door was locked, so he waited in the entranceway for a long time, hoping someone would open the door and he could enter. After he finally got in, he found the right apartment and knocked at the door, but nobody answered. Although the building was huge, there was no sign of life, so there was nobody to ask for help.

At a certain point, R’ Biderman began to give up. He started walking to the exit as he wondered whether the address was even correct. If it wasn’t, how would he ever find the woman and in so short a time?

He was ready to go down the stairs when he noticed an elderly woman slowly coming up. He went over to her and asked, “Do you know Mrs. Hillman?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Do you know where I can find her?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said, looking bewildered. “It’s me. What do you want?”

It was like a big rock rolled off his heart and he sighed with relief. He went with her into her home where he briefly told her about her childless cousin. He noticed how she grew pale as he added information, and her entire body trembled. When he finished, he wanted to hear what she had to say but she couldn’t utter a word. It was only when she calmed down that she was able to emotionally tell him what happened that day.

“Don’t ask,” she said. “Just today, I was thinking of my cousin in Canada and wondering how he was. Over the years we were somewhat in touch, but lately we were completely out of touch and I had no idea what happened to him. Then I come home and you tell me that he died and my signature is needed to bring him to Jewish burial.

“You should know,” she said, choking up, “there was really no chance of our meeting today because I was on vacation for the past week. I don’t have email and it’s very hard to reach me.

“Today, I just happened to remember that I forgot my umbrella and I came home just for a minute, to take my umbrella, and now we meet.”

After recovering from the initial shock, they went to the Chabad House and for two hours, they sat with the various documents which she signed with great emotion.

Only after she was sure that she had signed all that was necessary and that there were no problems that could crop up, did she leave. She asked R’ Biderman to update her on all developments. They agreed to keep in touch.

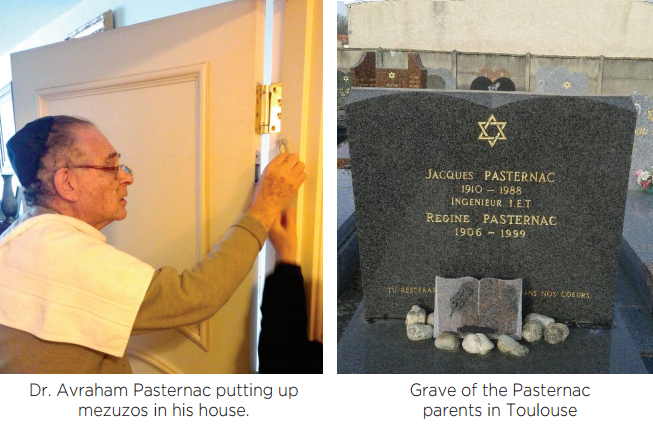

During their conversation, the cousin told of the deceased’s sad life. His Jewish name was Avraham Pasternac; his parents were Jewish, Holocaust survivors. When the cursed Germans conquered their city, they sent his parents and the rest of the Jews to Auschwitz. At the last moment, his parents were able to give him to a non-Jewish family who hid him for the duration of the war. For some reason, after the war, the parents were unable to locate the child and he continued growing up and living as a non-Jew. They went to Toulouse where they lived the rest of their lives until their passing.

R’ Biderman quickly reported to his colleague in Montreal with all the information he was told. R’ Silberstein was still dissatisfied.

“I’m sure you realize that before giving him a Jewish burial we need to verify his Jewish identity and not rely on simple hearsay,” he said.

PART III

With just a few details, including the names of the deceased’s parents, R’ Silberstein spoke to another shliach, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Matusof of Toulouse. R’ Matusof was willing to check things out and searched the computer database of the chevra kadisha in Toulouse. He soon found the name of the father. To his surprise, the mother’s name wasn’t there. This was exceedingly odd since if they were both Jews, they would have been buried next to one another. The fact that her name was missing was suspicious. Despite having verified the Jewish identity of the father, the Jewish mother’s identity also had to be verified.

R’ Matusof did research and learned that it was possible that the mother’s name did not appear in the registry of the chevra kadisha because if she was buried with her husband in a joint grave, they would only have registered the man’s name.

R’ Matusof called R’ Silberstein and the two shluchim agreed that this conclusion was doubtful, but the desire to bring the “meis mitzva” to burial gave them no rest. They knew that their job as shluchim was to fight not only for preserving Jewish life, but also for the Jewishness of the departed. They concluded that R’ Matusof would examine the grave.

R’ Matusof went to the cemetery which was locked, because it was years already that there was no room for additional burials. After much efforts he was allowed in and located the grave. To his delight, he discovered that both parents’ names were written on the stone: Yaakov and Rivka, along with the mother’s secular name, Regine.

Now it was clear that the childless man who died thousands of miles away from there was in fact Jewish. With this information, and with the consent of the cousin, the only living relative, R’ Silberstein quickly gave the documents to the hospital in order to get the body and bring it to burial.

PART IV

Suddenly, a will came to light, which the man had written a few years earlier, which referred to a Jew named Emil and asked him to take care of his burial when the time came.

R’ Silberstein felt this was the Satan’s work for, legally, in such a case, they needed to make sure there wasn’t another will written afterward that canceled the earlier will.

Another week went by until the relevant authorities concluded that there did not seem to be another will.

In the meantime, the Viennese cousin called every day or so to R’ Biderman to find out how the burial arrangements were coming along. After a few days in which the shluchim tried their utmost to arrange the paperwork, the woman said resignedly, “Fine, we did our part.”

A shliach is always on shlichus, so R’ Biderman took the opportunity to infuse some life into the living.

“One thing remains that you can do l’ilui nishmas the departed,” he told her.

“What is that?” she asked skeptically.

“Light Shabbos candles. I am sure this will be a nachas for his soul.”

The woman on the line was silent. She finally said, “The truth is that I thought of that. I’d be happy to do so if you teach me how. Do I extinguish the flames before I go to shul or leave them lit?”

The shliach was moved. He knew that the woman was far from being religiously observant and yet, not only did she light candles for Shabbos but even went to shul, and all because of what happened.

The shliach explained the mitzva to her.

PART V

On 7 Shevat, Dr. Avraham Pasternac had a Jewish burial in the Jewish cemetery in Montreal. Rabbi Levi Itkin, also a shliach in Montreal, heard the story of his burial and something rang a bell. He finally figured it out and he called R’ Silberstein.

“I know that man,” he said excitedly. “Although in the story that was publicized it said he had no connection with Judaism, you should know that I was in his house a while ago and put up mezuzos. We spoke occasionally; he was a deep thinker. I think he even put on tefillin one time.

“Throughout the years he was outwardly disconnected from Judaism, though he knew he was a Jew. He once sent a question to a rabbi: did the fact that his adopted family had him baptized cause a blemish to his Jewish soul? The rabbi answered that since it happened when he was a child, it meant nothing, and he was a Jew in every respect.”

The story made waves within the Jewish community in Montreal. “Thank to the deceased, some Jews here in the community committed to doing mitzvos l’ilui nishmaso,” said R’ Silberstein. “One person even committed to saying Kaddish for him.”

R’ Silberstein summed things up, “This story made a big kiddush Hashem. People saw how shluchim who knew neither the man nor his cousin, worked together to bring this man to Jewish burial.”

R’ Biderman says, “At some point, the elderly cousin tried to understand what connection I had to the deceased. She asked me whether I knew the man and I said no. She was amazed but said, ‘Oh, then the person who contacted you from Canada knew him …’ and I said no.

“When she finally realized what had happened, she concluded, ‘The rabbi in Montreal did not know him and you don’t know the rabbi in Montreal, and I don’t know you, but from heaven they made us meet so that my cousin, Dr. Avraham Pasternac, a lone Jew, would have a Jewish burial.”

“She was right in her summary but forgot to mention one other person who was involved – our Rebbe! If not for his shlichus revolution, this story would never have happened.”