The fascinating life story of Rabbi Shlomo Kabakov, mental health therapist and former photographer. * He grew up as a typical American kid in Manhattan, but his soul gave him no rest until he found what he was looking for, in Judaism. And then he discovered Chassidus, and one day, even discovered his Chabad roots.

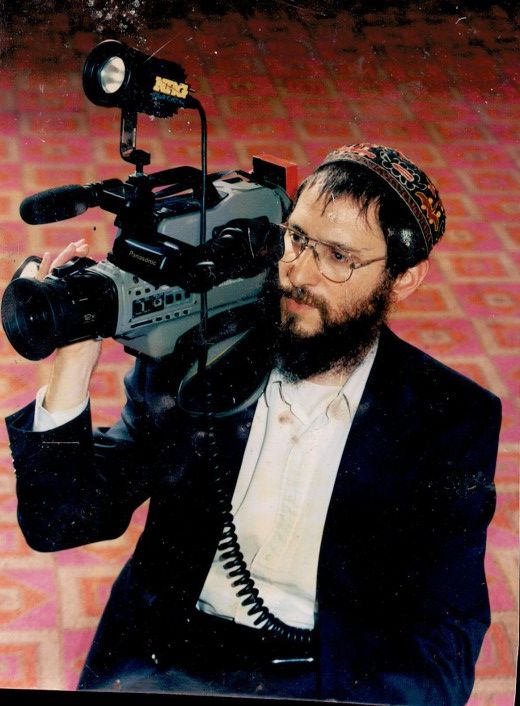

Directing an educational video

Directing an educational video

It was a long road that Rabbi Shlomo Kabakov of yishuv Nachliel took until he arrived at his life’s work. You can meet him in the public clinics of Bayit Cham and Leumit in the religious cities of Elad and Modiin Ilit as a mental health therapist. His attire lets you know he is a Chabad Chassid, but this does not in any way diminish the admiration people have for his work and devotion.

“A therapy session for me is a sort of farbrengen. The basis of the treatment is creating trust with the client, speaking one on one, listening, honesty, authenticity. Precisely the elements of a farbrengen. I have found work in which a great part of the day is spent farbrenging.”

R’ Kabakov’s hours are full of encounters with patients, as well as long meetings with colleagues, while pursuing continuing education in order to further develop his therapeutic approach. He is the kind of person who never rests.

CHILDHOOD IN MANHATTAN

Shlomo Kabakov was born over fifty years ago, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. When he was older, the family moved to the East Side of Manhattan. His father was an oncologist and his mother was a homemaker.

“Although we weren’t religious, we belonged to the Orthodox community led by Rabbi Haskel Lookstein. And although my parents were not religious, it was important to them that we preserve our Jewish identity, which is why they sent us to a Jewish school.

“For my bar mitzva, I was sent to prepare with Rabbi Rosenberg, the gabbai of the shul, a Chabad Chassid. He instilled in me values that stayed with me for many years to come. He spoke to me in a straightforward way, and I remember that I loved to go and learn with him.”

Along with his bar mitzva lessons, his parents fulfilled his dream and gave him photography equipment and a darkroom to develop photos as their bar mitzva present to him.

“Since I’ve been a kid, I’ve loved photography. I would walk around the streets of New York and take pictures. While going to school, I developed this hobby and turned it into a profession. I held exhibits of my photos in coffee houses and there was great interest in them. I especially enjoyed photographing street scenes.”

His sister went to a religious school in Manhattan and became very religious and this had an influence on the rest of the family. Their home changed a lot thanks to her. His father who was barely home on Shabbos because of work at the hospital, started staying home on Shabbos and even held Shabbos meals. The sister then flew to Eretz Yisroel to attend a religious seminary and she eventually married Rabbi Danny Cohen, rav in Bat Ayin.

“It took me more time,” says Shlomo. “I found my inner peace on trips and the long hikes I did in the forests and mountains around New York. I loved contemplating nature and its beauty.”

R’ Kabakov says he realized that Jews are unique. He saw this, for example, in his father’s Jewish humor, that no outsider could really appreciate. At a certain point he even wanted to become religious, but for a long time there was nobody to guide him.

“Photography and hiking gave me great satisfaction, but whenever I finished a hike or exhibition, I was struck by a sense of emptiness. The one who encouraged me to go to Eretz Yisroel was my older sister, who registered me in Aish Ha’Torah. I was eighteen.”

DISCOVERING CHASSIDUS

R’ Kabakov studied in Aish HaTorah for a year and became a baal teshuva. “I felt how Torah study changed me.” Then he transferred to the Litvish yeshiva Darche Noam in Kiryat Moshe in Yerushalayim.

“Despite the many hours of learning and the feeling that I had found my place, I still felt some dissatisfaction. When I became exposed to sifrei Chassidus and attended a Tanya shiur for the first time, which was organized in stealth, I realized that I had finally found what I was looking for. But I still did not have the courage to change.”

Shlomo married in 5744 and settled in Romema in Yerushalayim. To earn a living, he went back to his hobby and began offering his services as an event photographer. He was hired to photograph an event that was held by the Chabad Shamir organization. “By divine providence, a few days earlier, my chavrusa gave me the book by R’ Lazer Nannes, ‘Subbota,’ as a gift. The book stuck out of my coat pocket.

“Rabbi Yitzchok Kogan, who welcomed me at the event, noticed the book and made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. ‘Do you want to meet the author?’ I was surprised and very happy. He arranged a meeting with R’ Lazer Nannes. R’ Nannes told me that he knew a Chassid of the Rebbe Rashab whose name was Kabakov, the same as my name, who was a lumber merchant. He even told me that in the first group of students in Yeshivas Tomchei T’mimim in Lubavitch, there were seven bachurim there by the name of Kabakov.

“I connected to him very much, and after that, every week we would meet to learn Tanya together. I quickly realized that this is what my soul yearned for all those years. R’ Nannes epitomized the image of an early Chassid filled with Jewish soul powers the likes of which I had never seen. When my father came to visit me, I had him meet R’ Nannes.”

MY FATHER AND CHABAD CHASSIDIM

After realizing that the Kabakov family likely had roots in Lubavitch, Shlomo relayed this to his father and was surprised to hear how much his father admired the Rebbe. This was something that, for some reason, he had not heard about before.

“As a senior doctor (he worked as a senior doctor at Beth Israel hospital for several years), he was the doctor to many Lubavitcher Chassidim. He once told me that there was a Lubavitcher girl who came to his department in a coma. His professional opinion was that if there was no medical intervention, she would not survive. And even if they did treat her, her chances of surviving were, at most, 50%.

“Her parents told the medical team that before they made a decision, they would ask the Rebbe. To my father’s amazement, and the amazement of the medical team, the Rebbe suggested they wait ten days. My father said he was very skeptical, but on the morning of the tenth day the girl opened her eyes and her condition improved without any medical intervention.”

The younger Kabakov family moved to Har Nof and R’ Shlomo looked for a place to daven. A friend recommended a Chabad shul. “There is a farbrengen after the davening on Shabbos,” he said.

“When I went to the shul, I immediately knew this was the place I wanted to daven in. Not only was the chulent at the farbrengens great, but so were the Chassidim I met there. I learned a lot from them. They gave me the right tools for life. At that time, R’ Boruch Kaplan founded a yeshiva program for English speakers and I began learning Chassidus together with Rabbi Shlomo Mann. I also learned a lot from Rabbi Moshe Vishnefsky and Rabbi Moshe Miller. I learned with all of them and gained a lot; they turned me into a Chabad Chassid.

“I saw people who don’t put on any shows, and all of their davening and learning is done sedately and with inner thought. When I learned Chassidus, I realized where this came from.”

At the same time, R’ Kabakov studied Gemara with a chavrusa. The chavrusa was shocked by the change in his friend and was not willing to concede so quickly. They got into frequent debates. “His questions had to do with various Chabad practices. Thanks to him, I gained a thorough knowledge of Chabad customs along with their sources and details, and it was all in order to know how to respond.

“One day, the rosh yeshiva came over to me and said he heard that the Rebbe announced that girls also need to learn Torah and this surprised him. I happened to have the sicha on me and I gave it to him to learn. He took the sicha and came back to me the next day and said, ‘I completely agree with the Rebbe.’”

ENCOUNTER

WITH THE REBBE

For Shavuos 5747, still in their early days of connection to Chabad, the Kabakov couple flew with their two little children to the Rebbe.

“At that time, my wife was feeling that she is sacrificing her own life for the sake of raising the children. For a young mother who was not yet used to it, it was very difficult. She thought she would ask the Rebbe about it at ‘dollars.’ As the line progressed, she felt more embarrassed and decided that she would not bother the Rebbe with such ‘foolishness,’ in her words, and she left the line.

“A number of Chabad ladies who heard from her that she had decided to quit the line, refused to leave her alone until they convinced her to rejoin the line. She passed by the Rebbe with our son Binyamin in her arms. The Rebbe gave a broad smile and pushed a dollar into his hand. My wife turned to continue walking, but suddenly she said to the Rebbe, ‘Me too?’ The Rebbe answered, ‘You too,’ and gave her a dollar. Those two words that she heard from the Rebbe dissolved all the feelings of hardship. Those words have accompanied her ever since, and whenever she has thoughts of lesser worth, she feels the Rebbe telling her that she too is valuable.”

EDUCATIONAL FILMS

R’ Kabakov was one of the first to produce educational films for children in the religious sector. His films, which have been seen by tens of thousands, have become standard fare for children growing up today in the Chareidi world.

“At a certain point, I decided to use my photographic skill to do something meaningful that would impact on the maximum number of people. I focused mainly on humor, which has the greatest influence on children. My first film told the story of a boy from a poor family who finds some money, but he knows that he should return it to its rightful owner. The film shows his inner struggles. I produced many more films and they all contain educational messages.”

NEW JOB HELPING JEWS

When he reached the age of forty, R’ Kabakov experienced a personal crisis. “I felt that everything I was doing did not give me inner satisfaction. I thought about my father the doctor, my two sisters who are social workers, and a brother who is a pioneer in services for the deaf and blind. And what about me? I felt that I had to make a career change. I wrote to the Rebbe and received an amazing answer in the Igros Kodesh. The Rebbe writes there that the world stands on Torah, Avoda (prayer), and Gemillas Chassadim (acts of kindness), and that in our generation there is a greater need for acts of kindness.”

R’ Kabakov felt that this was a clear and direct bracha from the Rebbe to study a profession that would give him the tools to help Jews. He flew to New York and went back to being a student, completing a degree in social work. Today he works as a social worker, doing individual, marriage and family therapy. He has also since completed a Masters degree from Bar Ilan University in social work, training for trauma therapy in Machon Cheiruv, and training for family therapy in Machon Lamishpacha. He provides individual counseling using CBT, guided visualization, support therapy, as well as dealing with anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

What exactly is your job? How would you define it?

I would categorize myself as someone who treats “minor” psychiatric conditions, which include issues of self-image, self-confidence, anxieties and traumas. A person who walks around for a long time with the feeling that he is not okay and his environment is not treating him right, is likely to experience anxiety, and I am there to help him figure out his place in the world. I teach him how to get himself out of that rut. In most cases, anxieties are not inherent, they are acquired.

How does an ordinary person determine that a given struggle is not simply a passing thing, but an anxiety that requires treatment?

Generally, a person comes for counseling when his daily functioning is compromised. If a person doesn’t leave his house, we all understand that there is a problem. The indication that the problem is acute is when the person ceases to function. A medical doctor will never be able to diagnose a problem if the person sitting opposite him is functioning at one hundred percent. The same applies to psychology. It is only when a person has difficulty completing tasks that he used to manage easily that we know that he is in distress.

What are the most common emotional problems?

Social anxiety. People convince themselves that the other person harbors ill will towards them, or sometimes people for whatever reason feel that they are not accepted socially. This will generally occur when a person tries too hard to impress others. For example, a yeshiva student who decides to be extremely pious mostly for social reasons and did not succeed in impressing people or did not get the feedback that he thought he would receive; then comes the crash. Truthfully, it is hard to pull yourself out of it. A lot of social anxiety also comes from perfectionism.

What tools do you use in treatment?

I have in my arsenal two main approaches. One is CBT. I question the person to find what interpretation they apply to their situations and understand from that how that interpretation is the source of the challenges, and then work to change them. For example, a person who lives in an environment of endless conflict will interpret certain situations differently than someone who lives in a tranquil environment. This approach is similar to the saying of the Tzemach Tzedek, “Think good and it will be good.” Or more accurately, the teaching of the Baal Shem Tov, “In the place where a person’s thoughts are, that is where he is.”

In recent years, I studied an additional approach called IFS, developed by Richard Schwartz. He argues that a person at his core is essentially pure and good, but that childhood experiences may cause different internal responses from the person. A person might find himself avoiding certain actions or creating certain situations as a result of the internal conflicts of this inner construct.

You identify openly as Chabad in a decidedly Litvishe environment. How do they accept you?

Quite well. I never encountered any difficulty related to this subject. I do my work in a professional manner. When somebody has psychological problems, he needs someone with expertise in psychology. I have great respect for the demographic that I work with, and the fact that I am Chabad has no bearing on how they relate to me.

Does the fact that you are a Chabad Chassid and study Chassidus help you in your work in any way?

Chassidus is built on understanding the inner workings of the soul. That is the subject matter that Tanya addresses. For example, when the Alter Rebbe writes about making an accounting of the soul, he is not referring to making a list of all the sins and transgressions that we committed. Rather, he is talking about the need to discern where we are holding and what state we are in, which is basically what a therapist does. He has to ascertain the state of the client and figure out why he is responding the way that he is.

There is a tremendously novel insight of the Alter Rebbe, in that he draws clear distinctions between the Good Inclination and the Evil Inclination. If a person acts inappropriately, that does not indicate that he is bad. His essence remains good, “but his inclination overpowered him.”

Many clients experience emotional and psychological hardships because they set the bar too high for themselves, and when they fall short they can find themselves in a crisis. People who suffer from perfectionism can very easily fall into negative cycles, and then I will often use the distinctions that the Alter Rebbe lays out between the tzaddik, beinoni and rasha. I explain to the person how far he is from being an actual tzaddik, which is normal, and therefore he needs to calm down. In general, when you learn Chassidus you have a better understanding of why things happen.

Nowadays, there is great awareness of the field of psychology. Never before did such a thing exist. We need to remember who started the whole thing – the Baal Shem Tov, and afterwards it was expounded upon in greater specificity in Chabad Chassidus. After it came down to the world in the writings of Chassidus, in vessels of Torah, it found different forms of expression in many different types of treatment. This is Geula, the times of Moshiach.

Freud, the father of modern psychology, came many years after the Baal Shem Tov who is the true founder of the psychological field. For example, the “mirror” concept of the Baal Shem Tov, which basically posits that the negatives that a person sees in another are issues that he needs to correct within himself. This treatment tool has a different name in psychology, projection, but it is the same idea. That is how Chassidus spreads in roundabout ways.