A soul descended into Lubavitch on 12 Tammuz 5640. A little boy, Yosef Yitzchok, was raised by his father while still benefiting from his grandfather’s input for his first three years. * Presented for Yud-Beis Tammuz.

PART I

Lubavitch

A small town in the Orsha district, previously in the Mohilev district, set in a magnificent area of rivers and fertile land. In the spring and summer there were verdant grass meadows. The homes were small and made of wood and the ground was muddy.

A small town but one known to tens of thousands. Its narrow paths were trodden by tens of thousands who came to the capital, to the jewel in the crown of Chabad.

This small town was the official residence of five generations of Chabad leaders. For 102 years, this town was the melting pot, the factory where Chassidishe neshamos were forged, starting from Cheshvan 5574 when the Mitteler Rebbe settled there and until Cheshvan 5676, when the Rebbe Rashab had to leave his ancestral land because of World War I.

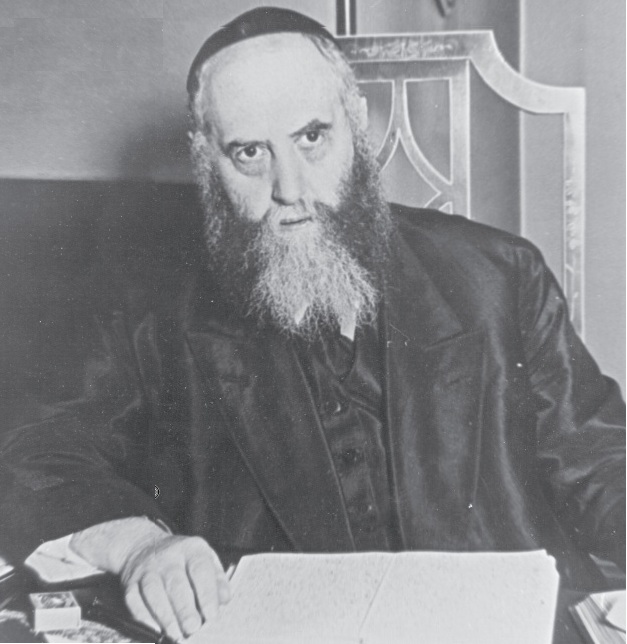

Here, in this rustic town, the soul of the Rebbe Rayatz descended on 12 Tammuz 5640, a Monday of the week of Parshas Pinchas, at 8:30 in the morning.

It was during the reign of the Rebbe Maharash, the fourth in the chain of Chabad leaders. The Rebbe was thrilled upon the birth of his grandson, son of his son, Sholom Dovber.

Friday night of Parshas Pinchas the shalom zachor was held and the Rebbe Maharash’s face glowed with joy. He told many stories and mentioned a few times that this Shabbos was a nidche since the fast of the 17th of Tammuz was postponed from this Shabbos. He concluded, “If only it were truly [i.e. permanently] cast aside,” as if he foresaw the terrible galus that would be cast upon the life of this newborn and wishing it on his behalf.

The baby’s bris was on 19 Tammuz. Like other babies, he cried. The Rebbe Maharash looked at the baby and said, “Why are you crying? When you grow up you will be a Rebbe (another version is: You will be a Chassid) and say Chassidus clearly.”

These few words seem to be the foundation of the chinuch of his grandson, a sort of ethical will, a way of life: don’t cry, don’t display ordinary emotions, withhold spontaneous emotions and channel them toward practical ends. Indeed, this is the path the grandson followed all his life, during times of joy and mainly, during terrible times of persecution and wandering. This is not the time to cry; take action!

During the seudas bris the Rebbe Maharash was also very joyous. He said a maamer Chassidus, told various stories and sang many niggunim, including the Alter Rebbe’s niggun of Four Bavos, which he sang with great solemnity and in a heartrending tone.

PART II

One of the fascinating educational tools the Rebbe Rashab used to groom his son was the method of “what do you remember” (this method has become accepted in the medical world). “My father would regularly ask me, from time to time in my younger years, ‘What do you remember?’ His intention was to refresh my memory of what I saw and heard in my childhood. The question, ‘What do you remember?’ was intentional so that I would remember what I saw in my childhood and so that an impression of the image would remain of the thing that I saw. These were events from times when I wasn’t yet capable of understanding the meaning of what I saw. Afterward, he would explain each thing.”

The question, “What do you remember,” was asked by the tzaddik Rabbi Boruch, the Alter Rebbe’s father, which is what the Baal Shem Tov asked him. The Baal Shem Tov asked this question of his other students too.

Snapshot #1

“What do you remember?” The Rebbe Rashab was walking with his son in 5646, arousing distant memories within him, hidden away in the psyche but etched in the soul.

The boy reviewed his thoughts, five or six years back, the images rush by one after another. A bed, maybe actually a red carriage, with two high sides at the foot and the head, with the side walls made of wooden slats. A small child, clear eyed and pure-hearted, the son of holy ones, lying on his back and caressing the slats with his hands.

Sometimes, the carriage was near a big bed. The baby gazed at the big wall that blocked his way. He already understood that someone lowered the right side at which time he quickly crawled out of his bed to the big bed where there was plenty of room to crawl from side to side. With sparkling eyes the baby scanned the ceiling of the large room, jealous of the big people who walked on their feet with no interference.

He also wanted to walk, to go wherever he pleased, to be free. He sought ways and ideas of how to get off the big bed, down to the wooden floor and crawl the length and width of the room. The child’s broad soul yearned for distant places … for spacious expanses … and the boy thought about it with his small mind and arrived at a conclusion. With his little fingers he pulled the side of the carriage which, with its small slats, looked like a small ladder, leaned on the big bed and managed to get down to the floor like one of the adults. “You cannot imagine how happy I was at this great victory. I was more than pleased…”

Apparently, the joy did not last long. The little one’s delicate and sensitive soul “understood” that every time the pillow fell on the floor, it suffered great pain from the fall and this made him cry lustily.

When he crawled for the first time on the little ladder, Yosef Yitzchok grasped the duvet on the big bed. When he got down, in his great joy he pulled the duvet down and at that moment the ladder fell and the duvet slid from the bed and pulled down the pillows that were on the bed. They all fell on the little baby.

His father listened to the memories of his firstborn, the first snapshot. His son made the effort and succeeded in recalling his thought processes as a one-year-old.

He got the idea of how to crawl out by thinking about what he saw. In a corner of the room, near the door, was a large oven. Every so often, he would see the adults putting something long into it, something that looked like the side of his carriage, like a ladder, on which the adults climbed in order to open the chimney vent. The image was absorbed, the method was internalized, and the baby’s brain turned it over in order to use it so he could get down, on his own, to the floor, like one of the grownups.

However, his first descent from his crib was unsuccessful and the pillows that fell scared him and he was ashamed and he received a few light slaps as “reward” for his mischief. Nevertheless, he was left with the means of how to independently get from where he was placed, to the bench.

PART III

In 5641, the Rebbe Maharash instructed that his house in Lubavitch should be enlarged. A special apartment was built for his middle son. It was completed in 5642 and R’ Sholom Dovber, his wife Shterna Sarah, and their son, Yosef Yitzchok, who was under the age of two, moved in. At this age, he began to grow under the watchful eyes of his holy grandfather and the discerning eyes of his father.

Snapshot #2

Young Yosef Yitzchok was in the big bed in the bedroom of his grandmother, Rebbetzin Rivka. The bed was near the wall, near the doorway to his grandfather’s room.

The door between the bedroom and the Rebbe Maharash’s yechidus room was open and Yosef Yitzchok gazed at the large room facing him. He saw a round table in the center of the room and near it sat a man who wasn’t tall. The child looked curiously at the handsome man. The man looked up and met the gaze of his beloved grandson and smiled and motioned with his hand. The boy, whether out of childish curiosity or obedience, immediately jumped from the bed and with small steps made his way through the door and entered the next room.

Without saying a word, the man took Yosef Yitzchok, placed him on the table, and gave him something gleaming to play with.

The images reach into the past, one following the other…

The Rebbe Rashab and his son, Rayatz, continued on their daily stroll in the resort town of Yalta. Seven-year-old Yosef Yitzchok talks, is quiet, rummages in the archives of his thoughts and tries to swim through the haze of early childhood, to filter the events and “bring up” the images that are branded permanently in the recesses of his soul.

“Whatever I would say, my father would ask me for more details,” writes the Rebbe Rayatz in his memoirs. “I think he accomplished two things: 1) that it should be clear to me what I remember and 2) that the memory should remain strong. When he spoke to me about something I remembered, he would ask me whether I remembered where the chair was and other trivial things like that, in his desire that what I remembered be fresh and clear, etched further in my memory.”

The Rebbe Rashab placed a loving hand on his son’s shoulder and in the silence of contemplation they walked side by side.

“What items were in the room?” his father suddenly asked.

“I remember that in the room were two big beds, one that was grandmother’s, which was near the wall leading to the carpentry area. The other bed was near the wall that led to the other room. Near the staircase was a small, round table and near it were high, yellow wooden chairs. In a corner of the room was a low, black box – an iron chest – and near the door leading to grandfather’s room was a red chest of drawers belonging to grandmother. Aside from that, I remember a big window overlooking the garden.”

“When you lay in bed,” asked the Rebbe Rashab, trying to refresh his memory, “what did you see out the window?”

“I saw the glass door and the little green-blue-red windows that comprised the glass room which led to the garden. The glass porch was painted in several colors. I also remember the chair painted blue that was on the small porch.”

“You describe that while lying in bed you saw through the door a man sitting in his room. What else did you see there?”

“I saw a large glass lamp hanging from the ceiling with many small lamps around it; a round table with many legs – usually the table was extended and became very long and then the legs were situated along the length of the table, but when the table was shortened, the legs were close to one another.”

“Father?”

“Yes, Yosef Yitzchok,” said his father as he looked lovingly at his only child.

“I remember another snippet.”

“Tell me, Yosef Yitzchok.”

“I mentioned the window before … I remember myself playing in the room. Next to the window was a table. I stood up on the chair and went from the chair to the table and from the table to the window … I played so much that I opened the window and being frightened I began to shout. I suddenly felt a tall adult pick me up from beneath and put me on the bed near the wall and strike me. That made me start to really scream. Some time afterward, you came into the room and took me by the hand and led me to the stairs. I don’t remember exactly. We walked to another room and then further, until the next stairs … until we came to a small, round, low house which had blue curtains with flowers. After that I don’t remember anything accurately.”

***

The sun was about to set when the Rebbe Rashab sat down on a nearby chair and his son sat facing him. He looked at his father questioningly, curiously, trying to understand. The Rebbe Rashab’s high forehead was furrowed. You could tell that he was “there,” back in the glory days when he was close to his great father.

“The man you saw was grandfather,” he suddenly said to his son and he added some details describing his appearance and what he wore. “It was Pesach Sheini 5642 when you were two months shy of two years old.

“At that time, there were important guests in Lubavitch. From Eretz Yisroel were R’ Leib Slonim and R’ Mordechai Dov Slonim; from White Russia were R’ Chaim Dov Vilensky, R’ Zalman Leibkes – Zlatapolsky – from Kremenchug, R’ Manish Moneson from Petersburg, and there were the ‘yoshvim’ who stayed in Lubavitch on a regular basis.

“That day, Pesach Sheini, after the davening, the guests entered Grandfather’s foyer and began to sing. Levik (the head servant) immediately went out and said the Rebbe told them to go to the Rebbetzin’s room and farbreng. We went to my mother’s room from the steps, sang and drank some mashke. About an hour later, my father came in and said a maamer Chassidus for a while. When he finished, he returned to his room while the others stayed to farbreng. I and Yaakov Mordechai Bespalov (the Rebbe Rashab’s friend and chavrusa) went to my room to review the new maamer we just heard. It was the maamer said on Shabbos with some additions, but every word of Grandfather had to be understood well.

“When we went to the room, you played and kept asking questions until I sent you to your mother’s room. They fed you and put you to sleep.

“When you woke up from your nap you would not wait until they took you out, but got out on your own and would walk around. You went to the ‘lobby room’ where you played with Aunt Mushka. She then left the room to help clean the table from the remains after the farbrengen. You remained in the room alone to play. You noticed a tree growing in the garden near the window with rabenes. They were white, no more than white beans. You got up on the window, played with the lock, and managed to open it and then you cried in fright.

“Chaim Meir the butcher was in the stairwell and at the sound of your cries he hurried into the room and saw you lying on the windowsill. He grabbed you and put you on the bed and gave you …

“In the meantime, Mushka came running to call me in a fright. I went into the room and took you by the hand and led you to our room. As we passed the stairwell my father [the Rebbe Maharash] opened the bedroom door and asked why you were crying. I told him what happened and he told me to come in with you to his room.

“Since he asked, I did so right away. I left you to stand with Mushka while I went to my room and took my gartel and then together we entered my father’s room. I remember how he sat at the table in the corner near the window, wearing glasses. When we entered, he took off his glasses and put them on the table. You went over to take the glasses but I took you and put you somewhere. Grandfather looked at you and blessed you.

“After all this, my father went out to the garden and asked that you and I go with him. We went past the sukka to the yard. We began walking along the row of trees and Grandfather told you to run ahead. You began to run but after a few steps you fell and immediately got up and nearly burst into tears, but Grandfather motioned to you with his finger around his nose and you remained silent.

“My father walked back and forth in the garden three or four times while I followed him and you pranced about as children do. He spoke to me the entire time. Then he went to the shed in the yard where he smoked a ready-made cigarette (not one you make yourself).

“That year the winter was mild and summer came earlier than usual, so that day, Pesach Sheini, was quite warm. My father would drink kvass (a fermented beverage) made from apples and he asked Bentzion the servant to bring him a cup.

“As my father and I were talking, you played among the flowerpots that were there. Leaves had started growing from one of them and you plucked a flower and gave it to your grandfather. I saw happiness and joy on his face from this gesture of yours. He wanted to tell you something but you were active and before he could open his mouth you had already run over to me and given me a flower too and my father laughed out loud in delight.

“In the meantime, Bentzion brought the apple kvass, a bottle and a cup, and put them on the iron table in the shed. Although you were playing all around, your eyes were constantly open to what was going on with Grandfather and me. When my father took the cup to drink and said a bracha, you came quickly and curiously looked into his mouth. Your gaze was suddenly caught by my father’s watch chain that he wore on his cloak. The watch had four strands of chain and you began to play with it. Again, my father laughed a lot.

“When my father wanted another drink, you made a move to indicate that you also wanted a drink. Grandfather said a bracha with you and you repeated each word quickly. He gave the cup into your two little hands but you gave it to me for me to drink first … Grandfather laughed heartily when you drank the kvass which you did not like. You gave back the cup and returned to your games.”

***

“When my father told me all this, the memory became more distinct for me and I remembered more about how my grandfather looked until his visage was etched in my mind, so that I now remember his entire image,” later said the Rebbe Rayatz.

PART IV

Snapshot #3

At that time Yosef Yitzchok recalled another memory:

“I remember that we sat on a bench near my grandmother’s apartment and I played. Suddenly, a black horse galloped into the yard with a man with long boots and a leather satchel on his neck. All at once there was a commotion. The rider jumped down from the horse and tied the horse to the fence and immediately went up the stairs to my grandfather’s room.”

“Yes, Yosef Yitzchok,” his father’s face lit up upon also remembering that scene. “At that time there was a wicked man like Haman in his time, who wanted to do evil to the Jews in Russia. My grandfather was Mordechai the tzaddik who annulled the terrible decree. The rider who arrived at a gallop was the messenger who brought the good news to my father and told him that his activities on behalf of the Jewish people were successful.”

PART V

Snapshot #4

Sounds of joy … Adults standing with various implements in their hands, one going like this with his hand, another like that. People are singing and are jumping up and down.

A small child, one month less than two years, stands on the window, jumping and dancing on his little legs. He also wants to walk over there, to the yard where many people are standing and dancing; to the sound of music, but alas, the glass window panes block his way there.

Only later did the boy find out that these were the wedding festivities of his uncle, R’ Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, youngest son of the Rebbe Maharash, who married Sarah the daughter of R’ Akiva Schreiber. It was Erev Shabbos after Shavuos 5642.

Snapshot #5

Through a tall window that Yosef Yitzchok loved to look out of, he saw the joyous celebration of his uncle’s wedding, and it was through that same window that he saw a large crowd gathered in the yard. The two-and-a-half-year-old boy did not understand what the sudden commotion was about, what was the reason for the ruckus and why there were changes going on in the house. He looked sadly at the people and wondered…

“Grown men walked back and forth and cried,” he described. The child was not allowed to walk freely around the house and was confined to the room, gazing out the window with questioning eyes.

It was only in later years that he found out that this was the time of the sudden passing of the Rebbe Maharash, at the early age of forty-nine.

As a child he did not yet understand that Lubavitch had experienced a tremendous tragedy like a bolt from the blue…